“All Knowledge Is Shared”

Broadening perspectives: As part of the Citizen Science program, scientists work together with citizens to conduct their research.

Current plans of the University of Bremen show how both sides are able to benefit. Thorsten Kluß from the Cognitive Neuroinformatics working group will make sensor technology available to beekeepers so that they can monitor their bee colonies. In return, the colonies will provide data that Kluß will use to gain insights into why the bees are dying out.

For years now, bees around the world have been mysteriously dying off in large numbers. Among other factors, scientists suspect the use of pesticides in agriculture as well as the so-called varroa mite, which afflicts the bees as a parasite. Because bees pollinate countless agricultural crops, the disappearance of bees is also a danger to agricultural yields. The Bremen “Bee Observer” project is providing valuable information on the welfare of bee populations in their hives that can be of use across the globe.

To get to the bottom of why bees are dying out, neuroinformatics expert Thorsten Kluß makes use of a method inspired by neuroscience. “All sensor data is correlated using algorithms. Using so-called data mining, we can collect information that would otherwise remain hidden in the individual data channels,” says Kluß. Similarly, the electric potential of the brain is evaluated via electroencephalograph, better known as EEG. “With this data, we can determine the number of bees and the amount of honey collected. We can also research the reasons for any diseases that crop up.”

The University’s Own Hives on Campus

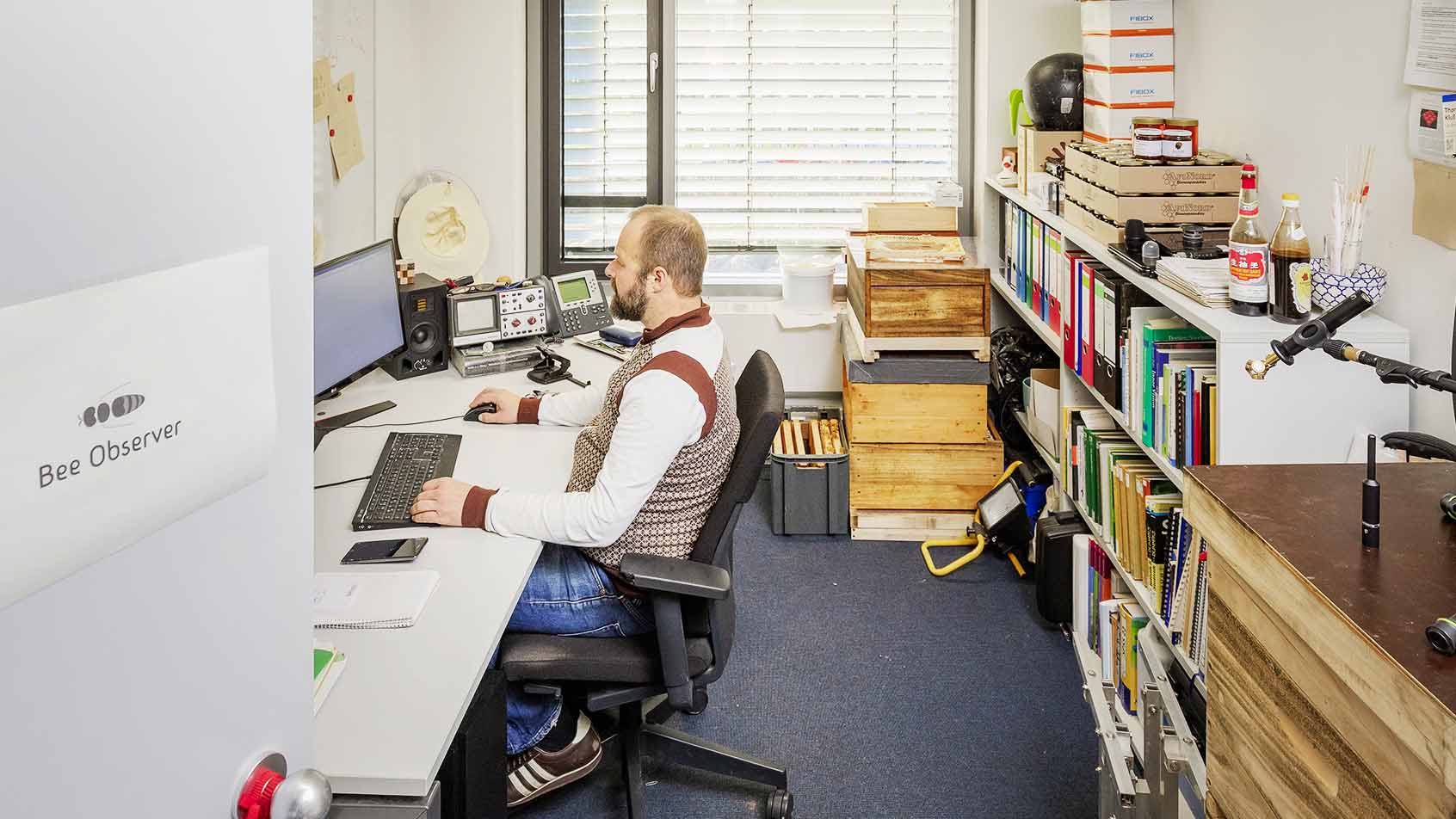

Kluß is fascinated by bees: “A bee colony is a unit – like a brain.” Together with his colleague, he came up with the idea of investigating the behavior of bees using neuroscientific methods. True to beekeeper parlance, Kluß calls the ten bee colonies in front of his office building on campus “hives.” “We equipped the hives with a series of sensors. We measure the weight, temperature, and humidity of the inside, as well as the airflow at the entrance and much more. To complete the data set, we also collect location-specific information like the weather.”

It was clear to Kluß from the very beginning that the Bee Observer project would only work with the knowledge and help of the population: “Which is why we keep in close contact with beekeepers from Bremen who are highly motivated in their work on the project. We are supporting them in something that is very close to their hearts.” Giving something back to the beekeepers is a key component of the project. “So we provide them with sensor packages that they can use to equip their hives, and 20 have already been fitted and are eagerly providing data.”

Honey farmers in Bremen can reap enormous benefits from this. Thorsten Kluß, who is also a beekeeper in his free time, knows precisely what can make their work easier. “Beekeepers make sacrifices to care for their bees and are always concerned whether the stored honey is sufficient and whether the colony will survive the winter. But if they check on how well the bees are doing and open the hives, the bee colony breaks out in a panic.” The colony would then need to put great effort into bringing the interior temperature back to 35°C every time. “It sounds like a paradox but, through the use of technology, we make beekeeping significantly more natural.” The scales installed in the hives enable the beekeepers to monitor the amount of honey without opening and disturbing the hives.

An Open Project for All

As part of the Citizen Science program, scientists work together with citizens to conduct their research. Current plans of the University of Bremen show how both sides are able to benefit. Thorsten Kluß from the Cognitive Neuroinformatics working group will make sensor technology available to beekeepers so that they can monitor their bee colonies. In return, the colonies will provide data that Kluß will use to gain insights into why the bees are dying out. Thorsten Kluß in the Botanic Garden with a Butterflx on his knee. © GfG/Universität Bremen From butterflies to bees: Thorsten Kluß’s research helps all insects.

For years now, bees around the world have been mysteriously dying off in large numbers. Among other factors, scientists suspect the use of pesticides in agriculture as well as the so-called varroa mite, which afflicts the bees as a parasite. Because bees pollinate countless agricultural crops, the disappearance of bees is also a danger to agricultural yields. The Bremen “Bee Observer” project is providing valuable information on the welfare of bee populations in their hives that can be of use across the globe.

To get to the bottom of why bees are dying out, neuroinformatics expert Thorsten Kluß makes use of a method inspired by neuroscience. “All sensor data is correlated using algorithms. Using so-called data mining, we can collect information that would otherwise remain hidden in the individual data channels,” says Kluß. Similarly, the electric potential of the brain is evaluated via electroencephalograph, better known as EEG. “With this data, we can determine the number of bees and the amount of honey collected. We can also research the reasons for any diseases that crop up.”

The University’s Own Hives on Campus

Kluß is fascinated by bees: “A bee colony is a unit – like a brain.” Together with his colleague, he came up with the idea of investigating the behavior of bees using neuroscientific methods. True to beekeeper parlance, Kluß calls the ten bee colonies in front of his office building on campus “hives.” “We equipped the hives with a series of sensors. We measure the weight, temperature, and humidity of the inside, as well as the airflow at the entrance and much more. To complete the data set, we also collect location-specific information like the weather.”

It was clear to Kluß from the very beginning that the Bee Observer project would only work with the knowledge and help of the population: “Which is why we keep in close contact with beekeepers from Bremen who are highly motivated in their work on the project. We are supporting them in something that is very close to their hearts.” Giving something back to the beekeepers is a key component of the project. “So we provide them with sensor packages that they can use to equip their hives, and 20 have already been fitted and are eagerly providing data.”

Honey farmers in Bremen can reap enormous benefits from this. Thorsten Kluß, who is also a beekeeper in his free time, knows precisely what can make their work easier. “Beekeepers make sacrifices to care for their bees and are always concerned whether the stored honey is sufficient and whether the colony will survive the winter. But if they check on how well the bees are doing and open the hives, the bee colony breaks out in a panic.” The colony would then need to put great effort into bringing the interior temperature back to 35°C every time. “It sounds like a paradox but, through the use of technology, we make beekeeping significantly more natural.” The scales installed in the hives enable the beekeepers to monitor the amount of honey without opening and disturbing the hives. An Open Project for All

“I was always a proponent of the concept of open source, which enables an open community to work together on a common topic. Anyone can make an impact, all knowledge is shared, and nothing is kept secret,” says Kluß. For this reason, he works closely with the so-called maker scene, where private individuals – from Bremen and the whole country – from the fields of technology, beekeeping, carpentry, programming, and engineering put their creativity to work to ensure that, in the future, every beekeeper will be able to download the instructions for the sensors and make them themselves. “There’s a lot of potential in a community like that. It generates ideas and solutions that I would have never thought of as an academic. Open-source educational research should become an integral part of the educational landscape, so that people around the world can take part and share in this knowledge,” says Kluß.