© Jens Lehmkühler

Climate Research on the Ocean Floor

The Bremen Cluster of Excellence “The Ocean Floor – Earth’s Uncharted Interface” investigates the function of the ocean floor as a climate archive

The ocean floor tells us stories from times long past which are most relevant for the future – those about global warming and changes in environmental conditions. With the help of specific biomarker molecules, Professor Dr. Kai-Uwe Hinrichs’ research group decodes material cycles from epochs of the highest climate dynamics as part of “The Ocean Floor – Earth’s Uncharted Interface” Cluster of Excellence – and at the same time researches how the carbon cycle has changed and could develop in the future.

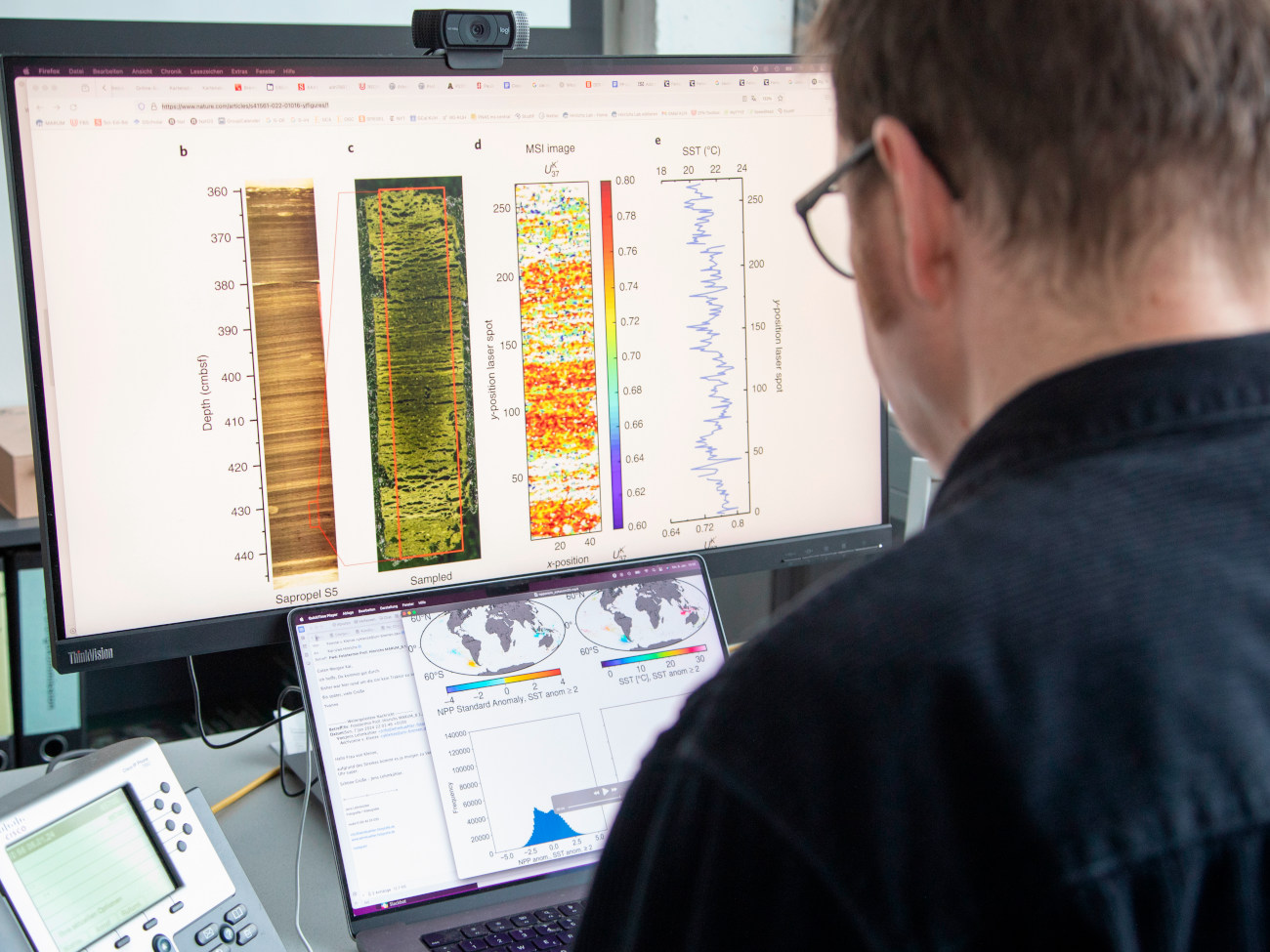

The image on Kai-Uwe Hinrichs’ computer screen is colorful. It shows the distribution of molecules within a small section of just a few centimeters of sediment core. The molecules reflect the surface temperatures of the ocean. Red stands for warm, green for cold – the temperature fluctuations of a period of about a century are visible at a glance.

© Jens Lehmkühler

The period under investigation is the most recent epoch of Earth’s history that was warmer than today, around 125,000 years ago. Such periods form a central research focus of the University of Bremen’s “The Ocean Floor” Cluster of Excellence. With the university’s MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, the Alfred Wegener Institute, the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, and the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research, this project includes four institutions of the U Bremen Research Alliance. “You have to go back a long time to find carbon dioxide concentrations comparable to those predicted for the coming century,” says Hinrichs. “These epochs from the past have a model character for the dynamics and interaction of future events.”

Hinrichs and his research group developed the imaging method, which shows high-resolution climate and environmental processes in the history of the earth. In some cases, the researchers can even extract information from the ocean floor samples month by month and read them like a climate diary. “We now also decipher the fine print in the sediment, which we couldn’t do before because we lacked the necessary tools,” says Hinrichs. The carriers of the information are the molecules that originate from dead seaweed from the past and are now made visible via the new imaging method. “They tell a story,” Hinrichs explains. The scientists are particularly interested in stories from turning point situations, from times of extreme climate change and temperatures or global disruptions of the carbon cycle. For example, during the largest mass extinction event in Earth’s history 252 million years ago, when massive environmental changes wiped out a large part of all marine life. Or during the last non-human-made global warming 11,700 years ago, when there was a drastic rise in temperature within a century or two. His research group determined how sea temperatures changed at that time.

The ocean floor not only serves as an archive for Bremen researchers. It is both a huge reservoir for carbon as well as a largely unexplored, extreme habitat for bacteria and their likewise unicellular relatives, archaea. It is estimated that around 90 percent of all bacteria and archaea on Earth are found in the subsurface of the ocean floor and the continents. They presumably play an important role for global material balances and the climate.

“The synergies in Bremen, the opportunities for development, and the support from the university are outstanding.” Prof. Dr. Kai-Uwe Hinrichs

A good 71 percent of the Earth’s solid surface is made up of the ocean floor, which lies on average 3,700 meters below the ocean surface. Huge amounts of CO2 are stored here for millions of years in the form of organic remnants of algae that have absorbed CO2 from the atmosphere at the sea surface. “We want to understand the natural processes,” says the biogeochemist. How exactly does the cycling of nutrients between the ocean floor and seawater work? What role do microbes play in this? How has the carbon cycle changed over time and what might it look like in the future? His research group and the Cluster of Excellence as a whole are investigating these and other fundamental questions.

© Jens Lehmkühler

Hinrichs and an international team have found microbial life even at a depth of 2.458 kilometers below the ocean crust, which is currently the record depth for the detection of microorganisms in the seafloor. Per milliliter of sediment, there are often well over one million cells that are still active even in 20 million-year-old sediments and, for example, convert the old organic material from algae and plants into methane. “The deeper you go, the slower the processes become. It’s a completely different world,” says Hinrichs.

The fact that the molecular decipherer examines the seafloor is no coincidence. Research on the deep biosphere is for the most part a new scientific territory. Little is known about individual inhabitants, their genetic diversity, their metabolism, and survival strategies. He certainly has an “explorer gene,” Hinrichs admits. In the late 1990s, while working as a postdoc at the renowned “Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution” in the USA, he discovered the microbes responsible for methane oxidation under oxygen-free conditions – a key process within the carbon cycle in the seafloor.

In 2002, the researcher, who received his doctorate from the University of Oldenburg, moved to the University of Bremen and MARUM as a professor of organic geochemistry. “The synergies in Bremen, the opportunities for development, and the support from the university are outstanding,” Hinrichs emphasizes. “I’ve always enjoyed working here.”

© Jens Lehmkühler

In 2009, Hinrichs secured the first of three grants from the European Research Council (ERC) with which the European Union supports cutting-edge research – a rare scientific achievement. With these and the funds from the Cluster of Excellence “The Ocean Floor – Earth’s Uncharted Interface,” Hinrichs built up his interdisciplinary international research group. It consists of more than 25 employees: chemists, biologists, oceanographers, geoecologists, geologists, and laboratory staff who work in several laboratories with state-of-the-art analysis equipment.

“When it comes to climate and marine sciences, we are in the same league as the top institutes in the USA.” Dr. Kai-Uwe Hinrichs

His most recent ERC grant project, entitled “Archean Park,” a synergy grant with three other scientists, received 11.5 million euros of funding. It takes Hinrichs back to the Archaic Age, to the origin of life 4,000 to 2,500 million years ago, when there was not yet oxygen in the atmosphere, but plenty of carbon dioxide. The researchers suspect that microorganisms can still be found today that prefer or even need extremely high CO2 concentrations. Beginning this summer, CO2-rich sites shaped by volcanic activity in the Czech Republic, Italy, and the Eifel will be explored. Of course, Hinrichs, who is also deputy head of the “Ocean Floor” Cluster of Excellence, wants to be part of the work on site: “This is something I wouldn’t want to miss!”

© Jens Lehmkühler

Funded by the federal and state governments, the cluster enables innovative research. It promotes scientific networking and interdisciplinary cooperation, acts as a magnet for young researchers, and makes further investments in infrastructure possible. In this way, it strengthens marine research in Bremen as one of the leading research locations in Germany. In 2025, a decision will be made on the continuation of the cluster, in which the University of Oldenburg will play a greater role in the scientific competition as a co-applicant. “In climate and marine sciences, we are in the same league as the top institutes in the USA,” says Hinrichs, who is also an elected member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. He is optimistic that with a very good application, the partner institutions will succeed together. However, the success in the competition is by no means guaranteed. “We have to do our homework very carefully like the first time.”

Historic Funding Success

In addition to Professor Hinrichs’ Archean Park project, two other climate and marine science research projects by member institutions of the U Bremen Research Alliance have been awarded funding from the renowned Synergy Grants of the European Research Council (ERC). In the “i2B” project, researchers are investigating, among other things, what an ice-free Arctic means for our environment and our society.

“PROTOS” examines the geochemical processes that took place at the beginning of Earth’s history. The aim is to investigate how life emerged from a world of water and minerals. Due to the success of these three projects, Bremen will receive 8.5 million euros in funding.

This article comes from Impact – The U Bremen Research Alliance science magazine

The University of Bremen and twelve non-university research institutes financed by the federal government cooperate within the U Bremen Research Alliance. The joint work spans across four high-profile areas and thus from “the deep sea into space.” Biannually, Impact science magazine (in German) provides an exciting insight into the effects of cooperative research in Bremen.