© Bàrbara Roviró

Connections Between Language and Fear

International Migrants Day: Romance language scholars in Bremen are investigating how an open approach to multilingualism can reduce fears

Only those who feel at ease can reach their full potential. Particularly in the school environment, successful learning is often hampered by uncertainty and fear. What role does language play in this context? Scholars in Bremen are researching this as part of the multinational and interdisciplinary network “Anxiety Culture.”

That didn’t go well. Suddenly the proverbial elephant in the room is there again. Teacher Max Mustermann sometimes has no idea why there is a sudden shift in the mood of his classroom. He had wanted to introduce his students to literature from other countries and as part of this, he memorized a Turkish poem and recited it in the original language. The Turkish children will surely enjoy this, or so he thought. But while some look at him with interest, a few students seem distraught. They seem to be sinking in their chairs. What happened? The scene described above is fictional and somewhat exaggerated. However, it illustrates quite well what Bremen linguist Bàrbara Roviró is advocating for – more linguistic and cultural sensitivity in the classroom. If Max had asked his students what language(s) they speak, he could have prevented this blunder. He would have known that some of the children he presumed to be Turkish actually have a Kurdish background, and that hearing the Turkish language definitely doesn’t make them excited, but rather leaves them feeling disregarded in their Kurdish identity. “If children and adolescents have experiences like this regularly, they do not feel properly seen. This can lead to discomfort and anxiety,” explains the researcher.

Heritage Languages Are a Great Treasure

Her experience suggests that scenarios like this are not uncommon in German classrooms. “A heritage language is a great treasure. However, this treasure usually receives little attention in everyday school life,” says Bàrbara Roviró. The Spanish language scholar studies the connection between migration, language, and fear in the University of Bremen’s Didactics of Romance Languages working group in Faculty 10 - Linguistics and Literary Studies. Central to her research are questions regarding how the Western world is addressing the multilingualism of migrants and whether this factor causes anxiety. The researcher takes it a step further to investigate the experience of those whose heritage language is not widespread.

© Andreas Grünewald

“Migrants who speak a minority language often experience a kind of double stigma,” explains Roviró. The first is due to most of them not yet speaking German very well, and the second is because their heritage language is not attributed to a strong national language and is therefore largely unknown.” They learn that people in Germany are not at all interested in their language and culture. It feels to them like this part of their identity is invisible and denied. This is unsettling and fuels fears in dealing with each other,” says Roviró.

Teacher Education: Raising Awareness of Multilingualism

This is a particularly serious problem for schoolchildren, as the fear of not being seen can negatively affect their learning opportunities and by extension their personal development. In order to minimize this risk, the topics of multilingualism and intercultural competence are permanently anchored in teaching degree programs at the University of Bremen. According to Roviró, this is not about revolutionizing the curriculum. “Teachers should simply act more naturally. Just ask instead of fighting and negating,” the teaching expert advises. Addressing the topic playfully in the classroom is also an option, for example, by mapping out which languages are represented by class members. “This opens completely new communication channels. The children feel seen as they are, which leads to more well-being and a better learning atmosphere. Such small measures cost nothing and bring so much,” says the researcher.

A Global Culture of Fear

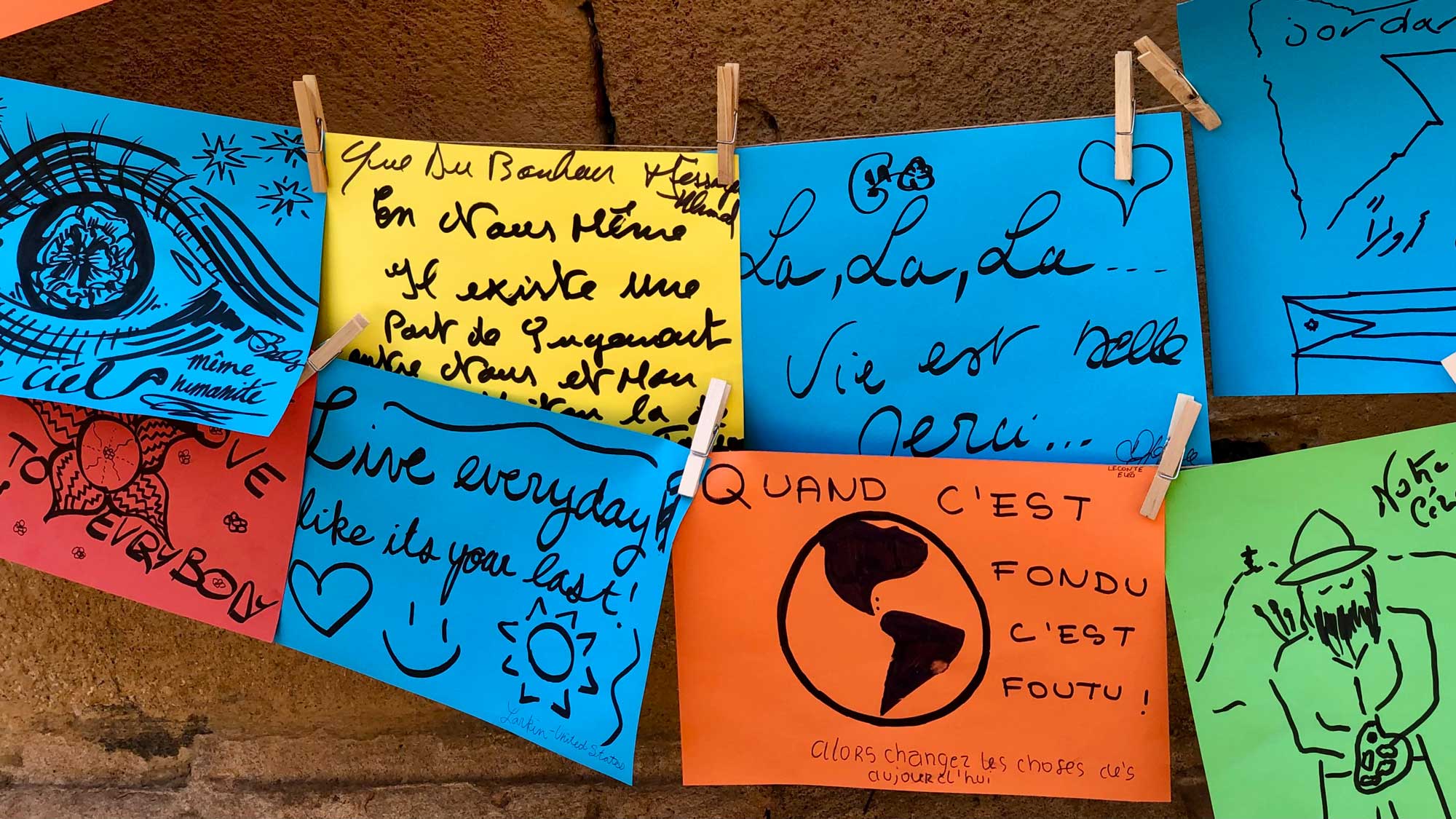

The researcher’s commitment to the topic of fear is not limited to the classroom setting. She is part of the multinational and interdisciplinary research project “Anxiety Culture” that includes about 30 social scientists and humanities scholars from Europe and the USA who are investigating collective fear and types of fear that occur at the societal level. They are convinced that many of the current global problems are fraught with fears, such as the climate catastrophe, the downward trend in the economy, or the rising strength of extreme forces in politics. They want to better understand how these are connected.

© Jan Rathke, Wirtschaftsförderung Bremen

They recently published their key findings in the book “Anxiety Culture – The New Global State of Human Affairs.” One of the editors is Bremen’s professor Karen Struve. The literary scholar is also one of the principal investigators in the long-term project. “One focus of my research are the narratives of collective fear,” says the Romance linguist. She’s trying to figure out how fear is even expressed. “The word ‘fear’ is Indo-European and means narrow, in the sense of a tightening of the throat and the associated inability to articulate oneself,” Struve describes. How do people still manage to express their fear? “Often through stories or through art,” explains Struve. She wants to gain a better understanding of what exactly happens in and through these tales.

Political scientists are also active in the Anxiety Culture network. They focus on discourses surrounding fear and how fear is articulated and used in politics, including how is it manipulated – for example in the debate about migration. “This is a very multifaceted topic with connections to many other areas. We are trying to gain as comprehensive of a view of this global phenomenon as possible,” says Struve. Bàrbara Roviró’s view on the topic of fear also focuses on the schoolchildren’s social environment. Her article in the book, titled “Multilingual Anxiety in Migration Contexts,” which she co-authored with Eva J. Daussà from the University of Amsterdam, not only addresses the connection between migration, multilingualism, and anxiety, but also explains concrete measures that could help. Born in Catalonia, she wants to sensitize society to the particular set of challenges faced by members of minority groups. “A sensitive approach to minority languages contributes to successful migration stories. I’m sure of that.”

Further Information

Anxiety Culture research project website

Website of the Didactics of Romanic Languages working group at the University of Bremen (in German only)

Website of the French Literature working group at the University of Bremen (in German only)