©Adobe Stock / Countrypixel

The Stable Revolution

The historian Dr. Veronika Settele has investigated the development of German agriculture between 1945 and 1990

Revolution in the Stable: Agricultural Livestock Keeping in Germany, 1945-1990 (“Revolution im Stall: Landwirtschaftliche Tierhaltung in Deutschland 1945-1990”) is the name of the dissertation by the historian Dr. Veronika Settele, who works at the University of Bremen within the History Department (Modern and Current History). Her work focusses on the emergence of both livestock farming and also the connected societal critique. In 2020, she received the German Thesis Prize (“Deutscher Studienpreis”). Additionally, she was also honored with the Opus Primum Prize for the best early-career researcher publication in 2020 from the Volkswagen Foundation.

Ms. Settele, you have investigated the development of agricultural livestock keeping between 1945 and 1990. How did you choose this topic?

The starting point was the observation that investigations into human-animal relationships were becoming a field of research in cultural science. A great deal of research on horses or pets was carried out, but hardly any on animals used in agriculture, despite the fact that they play a very large role both politically and economically in our society. As livestock farming was being increasingly politicized and discussed – animal welfare, meat consumption, vegan lifestyles etc. – the topic became ever more interesting to me.

Your investigations begins in 1945. Surely, pigs, cattle, and poultry used to still roam around the farm at that time – outside in the summer, in the stables in the winter?

© privat

The most important sectors are named with cattle/pigs/chickens. The keeping of animals was far less specialized back then. And it began during the period of food shortage after the war – the scarcity in society was also present in stables. There was a lack of feed and well-ventilated, dry stables where animals would not become unwell. There were often critical conditions in the stables: The animals vegetated, were fed badly in the winter, and the keeping of animals was hardly professionalized. Shortage meant that if it was bad for the people then that applied all the more to the animals.

How and who looked after the animals? Many young med from the countryside never returned from war and the conscripted foreign workers went home after the war had ended.

There were a great number of refugees and they were mainly accommodated in the countryside – many towns had been bombed. These people were needed. The keeping of animals back then was very, very work intensive and said work was not particularly attractive. That is something that is sometimes romanticized and idealized today, for example the milking of cows by hand. However, it is extremely tiresome if you have to milk several cows by hand twice a day. Hard graft was carried out from the early morning hours until late at night and the pay was very low – usually a mixture of board, lodging, and little money.

How did German agriculture develop in the period of quick economic recovery?

The period was increasingly characterized by a lack of workers. The quick recovery led to there being many far more attractive jobs that were cleaner and better paid. The class of “agricultural workers without possessions,” which were previously found around the farms and simply had always been there, suddenly shrank immensely.

“When women sold surplus eggs at the market, the ‘egg money’ was often their pocket money.”

Which role did technological development play in the first decades after the war?

The lack of workers was a central motor for the mechanization of agriculture. But that was not done from one day to the next – the agricultural industry is characterized by great lethargy. That is not my opinion but can be proven by the sources. Innovations, for example a milking machine or automatic feed machines, were initially met with skepticism. Too expensive, too difficult to clean, they do the animals no good etc. Both the political intentiol and the advice of agricultural experts was there and for creating more efficient livestock keeping. In the end, it was impossible to stop mechanization.

When did agriculture finally turn into an industry?

It’s not possible to say for all of “the agriculture” but it is possible for the poultry sector, for example. The sector was in the hands of women for a long time – often as a type of “female side job.” Chickens were kept for eggs and when the women sold surplus eggs at the market, the “egg money” was often their pocket money. Between 1963 and 1968 however, it turned into an industry. New automated techniques – battery cages or keeping the poultry concentrated in barns – were imported from the USA and were operated in accordance with business management principles. Eggs and poultry meat were able to be produced for little money throughout the whole year.

How did the animals fare during this change? Was the original “non-industrial” manner of keeping livestock on farms more suitable, as one assumes from today’s perspective? And how did the welfare of the animals change over the course of decades?

I cannot answer for the animals, as I am not a behavioral biologist. I already mentioned scarcity in connection to how humans treated animals in the time after the war. How should one spend money on better stables if there is not even enough for new shoes for the children? However, those who keep animals for agricultural purposes generally view themselves as responsible people who wish to treat the animals well – animal cruelty was frowned upon and punished. What is interesting is the viewpoint that an animal is doing well as long as it lays eggs, its muscles are growing, or it produces enough milk. It was only at the end of the 1970s that the field of behavioral biology was listened to more when it said that this is not necessarily the case.

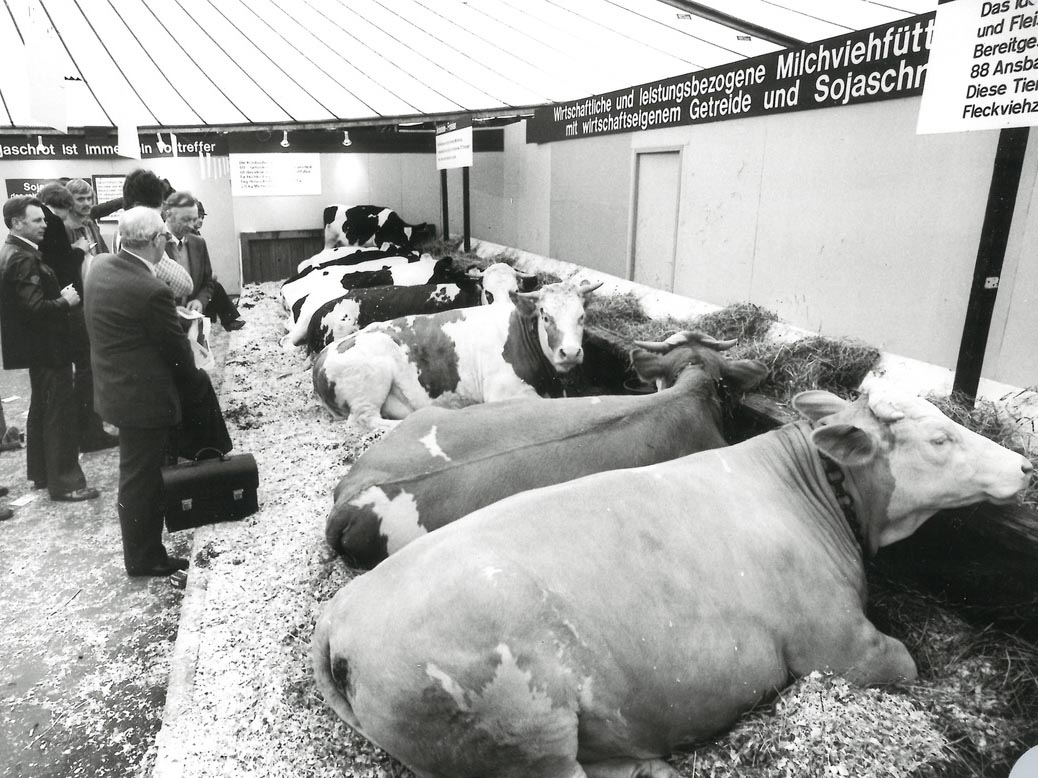

© Archiv der DLG, Frankfurt am Main

When were the first protests against intensive livestock keeping with a focus on animal welfare – and how have they developed over time?

It began at the end of the 1960s when large poultry houses with cages were rebuilt. The protests really gained momentum in the 1970s. However, the whole animal welfare debate focused on caged chickens until the 1990s. It is rather the pigs that form the core of the debate today, although bull rearing is also unpleasant to see.

“The bodies of animals are in a position to provide the goods that the consumer society desires in ever shorter timeframes.”

In terms of the GDR, the agriculture there was massively state-controlled. What was different there in comparison to the Federal Republic, and what did it mean for the country in the period until 1990?

Animals that did not belong to you – such as in the agricultural production cooperatives – were generally in a worse condition in the GDR than the few animals that were allowed to be held privately. Apart from this, I found out that the similarities between the Federal Republic and the GDR in this sense are more comprehensive than one would think. If you expediently look for differences, you find them of course – but in terms of working steps or mechanization, there are clear parallels. What was definitely around in the GDR was the direct arm of the state in the stables. Decisions were made on the basis of political stipulations and not agricultural understanding.

Your research sheds light on the period until 1990, but you have surely taken a look at the further developments in agriculture in the following 30 years up until today. What is this period characterized by?

A further development of the strategies adopted until 1990. The physical optimization of the animals – the industry call it “breeding progress” – is increasing. The bodies of animals are in a position to provide the goods that the consumer society desires in ever-shorter timeframes. The economic viability of companies has continued to increase thanks to mechanization and growing stables. On the other hand, we are witnessing an animal welfare movement in society that has only really gained momentum in recent years. Much differently to in 1990, there are now alternative forms of livestock keeping – they are becoming increasingly more significant. However, I still feel there is great room for improvement. It has taken up more space rhetorically than it has in reality.