“It Is Writing Against Scholarly Opinion”

Historians at the University of Bremen are delving into the topic of slavery in the Old Empire

Since the 19th century, historians have maintained that slavery did not exist as a legal institution in early modern Germany. In 2017, one of their number, Professor Rebekka von Mallinckrodt, found strong evidence to the contrary. In the research project “The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and its Slaves,” she and her team are examining the extent and significance of human trafficking in the Old Empire.

“Our notion of slavery is strongly influenced by plantation slavery in North and South America,” Rebekka von Mallinckrodt, professor of early modern history at the University of Bremen, explains. “We assume that slaves were people who worked in their hundreds of thousands in sugar and cotton fields. This type of slavery did not exist here.” In the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation – under the rule of the Holy Roman Emperor from the Late Middle Ages to 1806 – it involved enslaved individuals or groups belonging to the household.

No Slave Laws in the Holy Roman Empire

In an essay on ‘Slavery and Western Civilization’, the renowned historian Professor Jürgen Osterhammel asserted as late as 2000 that: “There were slaves elsewhere; there were none in Germany. For Germans they were a long way away.” According to Mallinckrodt, the reason for this assumption was the absence of any legal basis for slavery in the Holy Roman Empire. “Researchers assumed that, because there was no legal status for slavery, there were no slaves.” Although people of African descent did indeed live in the German territories, historians argued that they had been “rescued” and “bought and freed”, or given servant status. “Researchers frequently assumed that these people were freed through baptism or by arriving in the Empire.”

“The cases show that the institution of slavery legally existed.”

In documents relating to a petition and court proceedings from Brandenburg-Prussia and the Principality of Lippe, Rebekka von Mallinckrodt found evidence that slavery certainly did exist as a legal institution in the Holy Roman Empire. “The cases demonstrated that ownership rights were expressly and emphatically claimed and confirmed by the judicial system, the administration and the sovereign. They show that the institution of slavery legally existed.” Both cases involved men abducted from Africa, whose petition or suit obliged courts and legal experts to comment explicitly on slavery.

Conflict Cases as Evidence

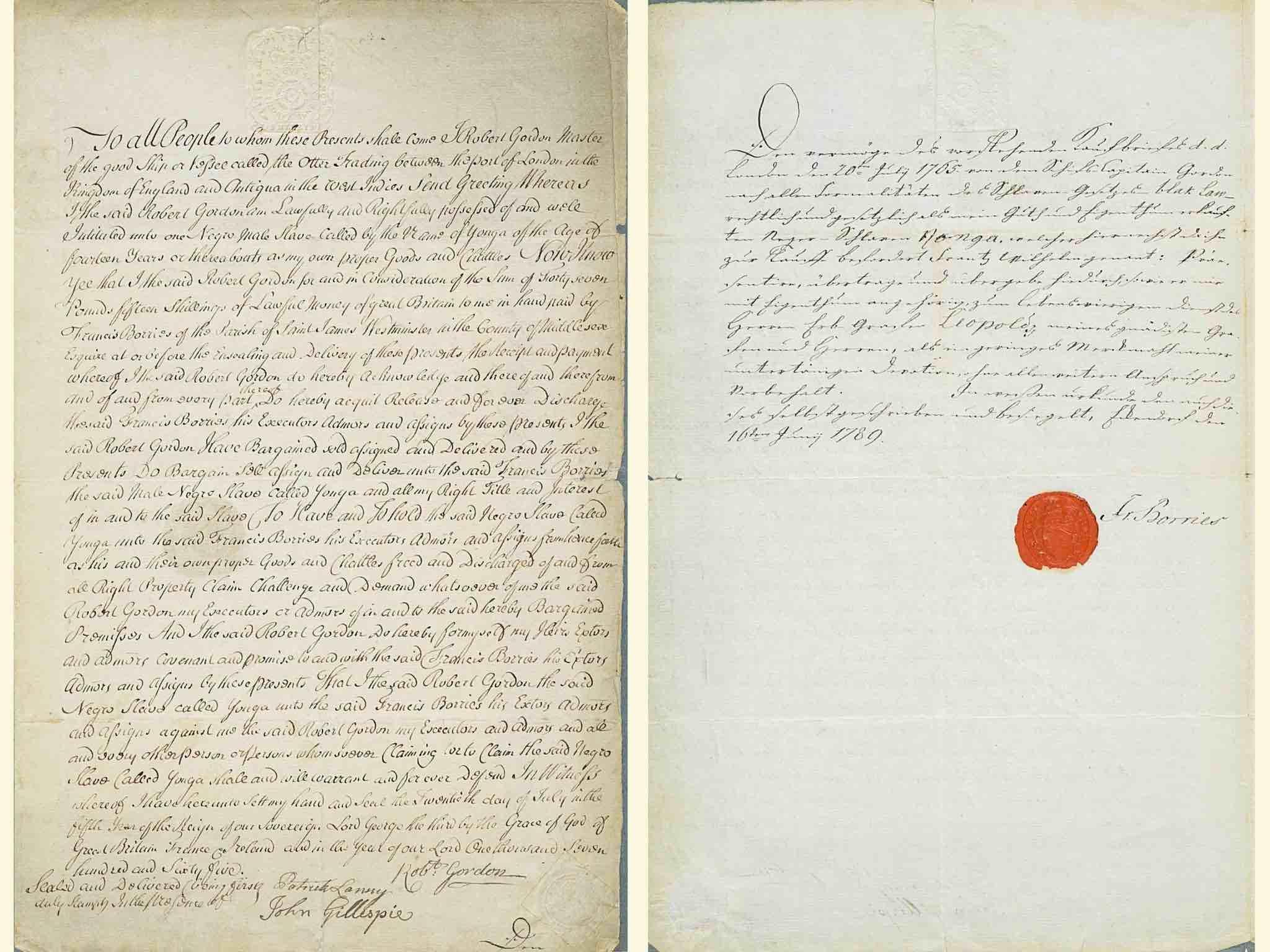

The first case – known to researchers as the “Legal History of a Purchased Moor”– dealt with a man, who remains nameless in the sources, held as a slave by the Prussian official Joachim Erdmann von Arnim (1741-1804) who in 1780 petitioned the King of Prussia, Frederic II (1712– 1786) to avoid his resale. The legal experts from the Supreme Court of Berlin explained that the possession of slaves was permitted under natural law and that the petitioner could be legally resold by Arnim. The second case arose in the Principality of Lippe. In 1790, the black servant Franz Wilhelm Yonga (approx. 1751–1798) filed suit before the highest Lippian court against his former master and owner, privy councilor Franz Christian von Borries (1723–1795). The reason for this was Yonga being gifted to Count Leopold zur Lippe in 1789. Von Borries had purchased Yonga as a fourteen year old in London from a ship’s captain, had him baptized, and put him to work as a hairdresser and servant in his household. Yonga believed himself to have been freed by baptism, even though he received no wages throughout his years of service. In his own words, it was the hope of being taken care of in old age that helped him endure.

“Slavery and serfdom are distinctly dif ferent from each other, and it is a distinction that contemporaries also make.”

Before the court, von Borries upheld his entitlement to ownership and justified it with slavery: “[…], he was and remained a slave and my bondservant, also a purchased chattel, […] he was and remained my property, which I could sell, exchange, or give away at will, […].” In this case, too, the court finally agreed with the slave owner. “It argued that baptism did not generally lead to liberation and that there was no law in Germany that overruled the rights of servitude,” Mallinckrodt emphasizes.

The Difference: Slavery and Serfdom

There were indeed people in early modern Germany who were not free, who were forced to work, and were under the jurisdiction of their masters, namely serfs. However, von Mallinckrodt emphasizes the difference. “Slavery is clearly differentiated from serfdom by contemporaries: both amateurs as well as legal practitioners.” Serfs had a different legal status. “They were considered persons before the law and the right of subjects to take legal action had been in place since the German Peasants’ War in the 16th century. Not only did they have the option of taking legal action themselves, they could also testify as witnesses.”

Slaves, by contrast, were not persons from a purely legal point of view: they were “human chattels”. Unlike serfs, they generally did not have a local network of family or relatives, and therefore had no resources at their disposal in the event of a crisis or conflict, as von Mallinckrodt explains. It was a much more difficult situation than for serfs. “Among lawyers there was a very clear awareness that these were two different things.” Rebekka von Mallinckrodt describes her research as writing against scholarly opinion. Some colleagues react to her findings with skepticism because few such explicit sources have yet been discovered. For this reason it is important to find as many cases as possible. Refuting this skepticism however, is enormously motivating, because ultimately historical images of this kind are also important for today’s society. The historian and her team examine all different kinds of source in order to tell the story of slavery in Germany. In addition to written material, such as letters, invoices and court records, they also, for instance, consult paintings. “During the early modern period, portraits featuring black servants as ‘attendants’ to the person being portrayed were in fashion. We are now trying to find out, on the basis of housekeeping books, whether these figures were simply a painting topos or whether they represented actual individuals.”

Difficult Sources

However, the overall search for sources has been arduous. According to von Mallinckrodt, this is due first to the lack of structures. There was no compulsory registration of slaves in the Holy Roman Empire as in France and the Netherlands. Second, it is because the trafficked persons were so young. “Taking action at the start of their bondage was less possible, and their emotional dependence on their owners was greater than if they had been adults.” Therefore it is not surprising that ego documents, such as the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano in Great Britain, have not yet been found for early modern Germany.

Slaves in the Holy Roman Empire were often children. “Merchants, missionaries, diplomats, sailors and soldiers brought them back from their travels in the colonies or Africa as ‘exotic souvenirs’.” Once on European soil, the girls and (far more frequently) boys were often sold to members of the aristocracy at a substantial profit. “Unlike in the Americas, the purchase of slaves was less about labor,” Mallinckrodt points out. Prestige was the main motive of this human trafficking. This is indicated by the type of task to which they were put, their relatively high price, and the efforts involved in their acquisition. “Slaves were much more difficult to procure in Europe and more expensive than on the African Coast or in the colonies. Having an African to play the trumpet, set the table, or act as a carriage attendant for all to see was a status symbol, which, according to the historian, demonstrated wealth and social capital to one’s contemporaries. “It showed that I could afford this and had the necessary connections to get these people.”

“As Young and as Dark as Possible”

Historical sources, such as order letters sent to Amsterdam and Lisbon, relate the purchasers’ preferences. “In the majority of cases, children were preferred who were as young and dark as possible. The dark skin color was considered to be exotic, and the householders could show off how cosmopolitan they were.” According to von Mallinckrodt, there was a practical reason for the age of the children. “First of all, children were considered cute. In addition, they also learned the language quickly, were not perceived as threatening, and could be educated and shaped.” Particularly in the 18th century – the peak of the Atlantic slave trade – the purchase of children is verified by many examples, as the researcher explains.

Thus ship carpenter Martin Harnack bought a seven year old boy in Guinea and resold him in Prussia to the Königsberg officer Jakob Philipp Manitius (1698–1749) for one hundred Reichstaler. The purchase agreement states that Harnack transferred “the Moor boy as his previously bonded slave with all rights of bondage.” In 1752, two twelve year old, dark-skinned boys were “sent as a gift from Holland” to Count Ludwig Ferdinand von Wittgenstein-Berleburg (1712–1773). In 1734, the Abbess of Herford, Johanna Charlotte von Anhalt-Dessau (1682–1750) received the African boy who was later baptized “Carl Heinrich Leopold”. The “Soldier King” Friedrich Wilhelm I. (1713-1740), King in Prussia, also ordered and received boys from England. Rebekka von Mallinckrodt notes: “The people purchased as slaves were brought into the Old Empire and, it should be noted, resold or gifted there as a matter of course. This would not have been legally permitted with a serf.”

Information About the Project

“The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and its Slaves” project has been running since 2015. The total term of the project is five years. It is being funded by the European Research Council (ERC) to the amount of over one million euros. Two PhD students are writing their doctoral theses in the framework of the project, a historian is habilitating, and a database of trafficked people in the Old Empire is being constructed. The goal is to contribute systematically to a better understanding of the extent and significance of the abduction and enslavement of people in the Old Empire.