Marvels Made from Metal

A double-feature career: A graduate from the university and a Belgian guest scientist are inspired in Bremen by a new technology – and meet up again later on

Of course, any university would be proud of a success story like this one: A student and graduate first follows his path into research, then starts his own business, and later becomes the General Manager of the German location of a world market leader with its branch in Bremen. In turn, this leading world market company emerged from an idea that was substantially pursued at a university affiliated institute a good 30 years ago. A double-feature career – for people, and for the company. To be specific, we are referring to Marcus Joppe, the 3D-printing of metal, and the company Materialise.

“There was a train in the station and I wanted to be sitting in it – not waving at it as it passed me by.“ Marcus Joppe, Materialise GmbH

It was almost 30 years ago, when Computer Science student Marcus Joppe, who was in his third semester at the time, was looking for a student job at the University of Bremen. And he found one: from that point on, he would work with three dimensional design and production programs at the affiliated institute BIBA – Bremer Institut für Produktion und Logistik GmbH. He soon came into contact with 3D printing – 20 years before the hype around three dimensional printing really got started. “Hardly anyone believes me when I tell them that the first 3D-printing system in Europe was put into operation at BIBA in 1989”, Joppe says.

“It was fantastic technology, even back then”, he remembers. “Highly interesting for producing prototypes or sample designs.” It did however, still need to be developed quite a bit: “With the CAD-systems at that time, it would take one to two weeks to prepare printing jobs. Today it just takes minutes.” Someone needed to be able to recognize the possibilities of 3D printing and have a vision for the future. One person had that ability – Wilfried Vancraen from Belgium. The scientist from the University of Leuven was working together with BIBA as part of a European research project. During a visit there, he saw the first 3D printer. From that moment onward, he couldn’t get three dimensional printing out of his mind. After another half a year at the Belgian metal industry research institute, in 1990, Vancraen founded the company ‘Materialise’ in his home country. His goal: to forge ahead with the new technology.

Back to Marcus Joppe. He continued on his path as a scientist in Bremen – first with the student job at BIBA, then getting his Computer Science diploma at the same institute, becoming a research assistant there, and soon becoming the department head for 3D printing. He dedicated five years primarily to software development – because without data preparation and control technology to guarantee flawless production, the whole idea of three dimensional printing was just a beautiful dream. Eventually, Joppe became an entrepreneur, because there was something about the scientific field that inherently bothered him: “You achieve a research result by investing a lot of energy and dedication – and then the project is over and it often doesn’t continue any further.”

Seeing the Business Idea

But Marcus Joppe wanted it to continue: “I knew that we didn’t have to hide ourselves away with the BIBA software. I could already see the business idea.” In 2001, he founded Marcam Engineering GmbH, which specializes in 3D-printing software, initially with the strong support of BIBA. Joppe’s company soon began to grow steadily in the Bremer Innovations- und Technologiezentrum (BITZ), one of the first “start-up forges” for business promotion in Bremen. “We bet on the right niche, namely 3D-printing of metal. Plastic was already established at the time, but there were hardly any printed metal products on the market.” That slowly began to change – also thanks to Joppe’s company, which offered software support for the growing sector.

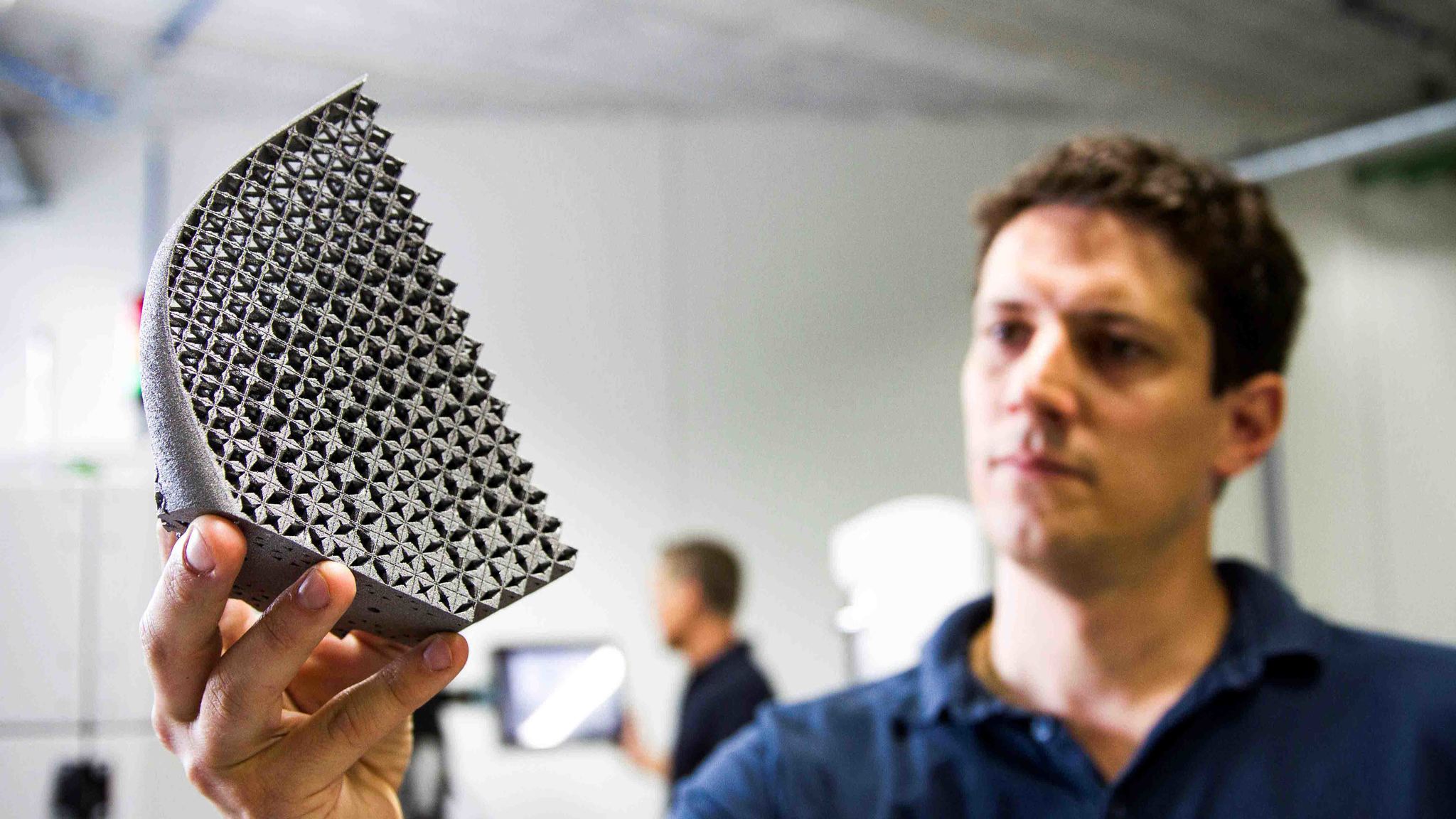

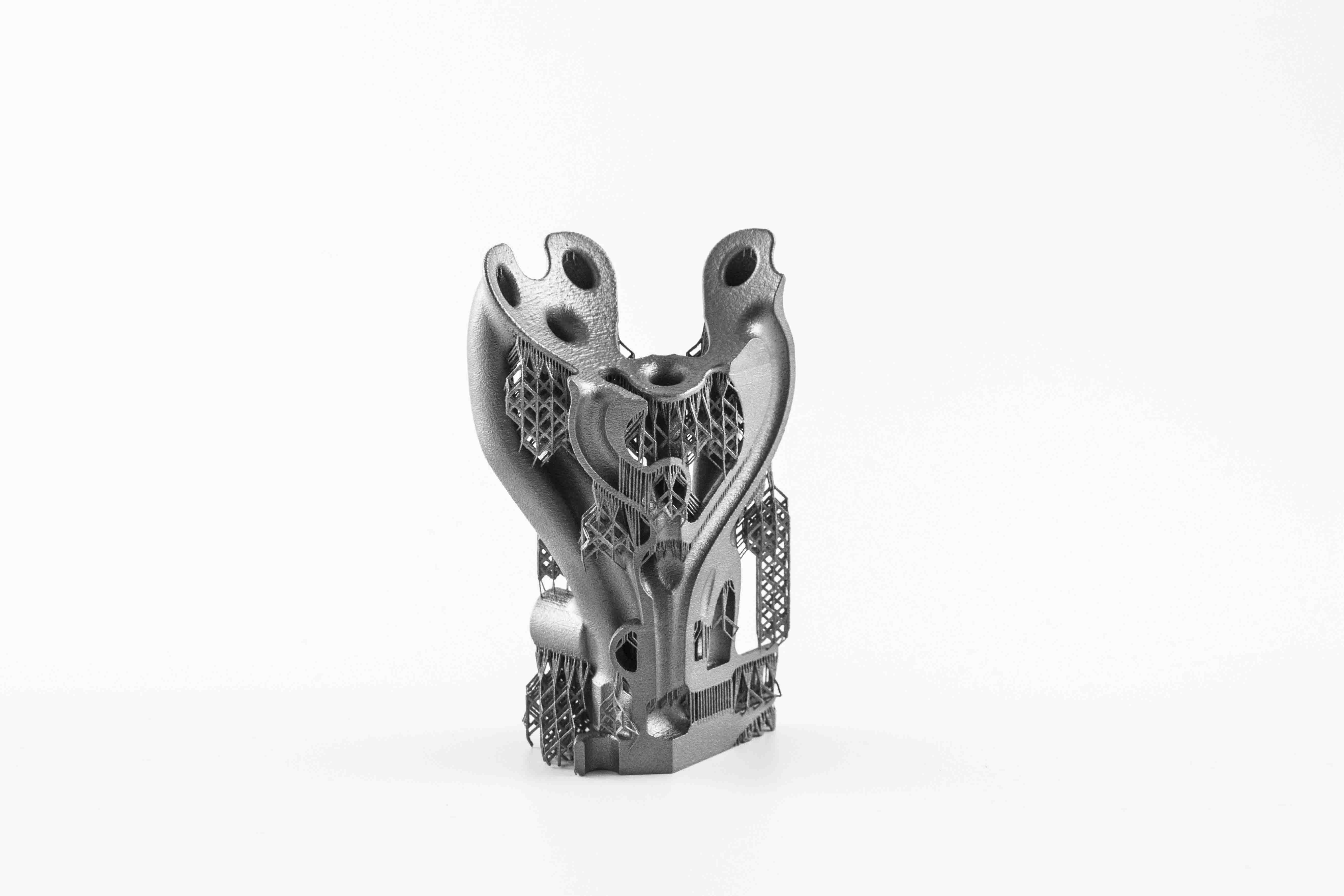

It soon became apparent that the printing of metal parts was highly interesting for certain fields. “You cannot drill a curved ventilation duct”, Joppe explains. “You can only drill straight. This exemplifies how metal 3D-printing enables the existence of completely innovative components – with a wealth of detail that is incomparable.” He presents a cage-like metal cube with exceptionally intricate structures inside it: “You cannot mill, cast or press something like this. It is only possible with 3D-printing.”

Around 2010, the worldwide boom of three dimensional printing began, also driven by the hype amongst stock market speculators.“Marcam was in a good position, but I had a feeling that the market was growing faster than we were. There was a train in the station and I wanted to be sitting in it – not waving at it as it passed me by.” Joppe began to look for partners. This is where the Vancraen from Belgium came into play: He had made Materialise big with a high level of competence in plastics, but not a lot of expertise when it came to metal printing. Both companies found each other, and in 2011, Marcam became part of Materialise. It even went back to BITZ: This is where the company opened a production location especially for the order production of components made from titanium and aluminum. One-offs, small series and prototypes were produced there for various sectors of industry, as well as for private clients – from extravagant pieces of jewelry, custom-made hip implants and transverse link suspensions for race cars, to certified production for the aerospace or automotive industry.

The 100 Threshold in Sight

The company has enjoyed great success. Eight years ago, when the university graduate’s company came to Materialise, Marcus Joppe had twelve employees. Today there are 75 employees, and the company is soon looking forward to breaking through the threshold of 100 employees. “It’s running smoothly”, says Marcus Joppe, delighted. He doesn’t get tired of emphasizing how valuable the accumulation of technical engineering know-how at the university and the technology park is to his company. BIBA, BIAS, IWT, BIMAQ, ISEMP, Fraunhofer-IFAM – these abbreviations stand for excellent scientific establishments full of bright individuals with impressive networks who collaborate closely with the user industry – such as Materialise, in this case. “When we have a challenge, we know who we need to ask right away”, says Joppe. “The specialists that we need in these moments are basically just around the corner in Bremen.”

It is a matter of fact that students and the next generation of scientists are in high demand at Materialise. And perhaps there is a young student who is only initially looking for a job, and who then continues along their path. The boss will certainly have some good advice for them.

3D-Printing of Metal: How Is it Done?

Three dimensional printing is no longer rocket science. There are already devices available for around 300 Euros for hobby household use with plastic wire as the material base. Yet highgrade industrial components are being printed with metal powder more frequently, which requires a lot of know-how and is still relatively expensive.

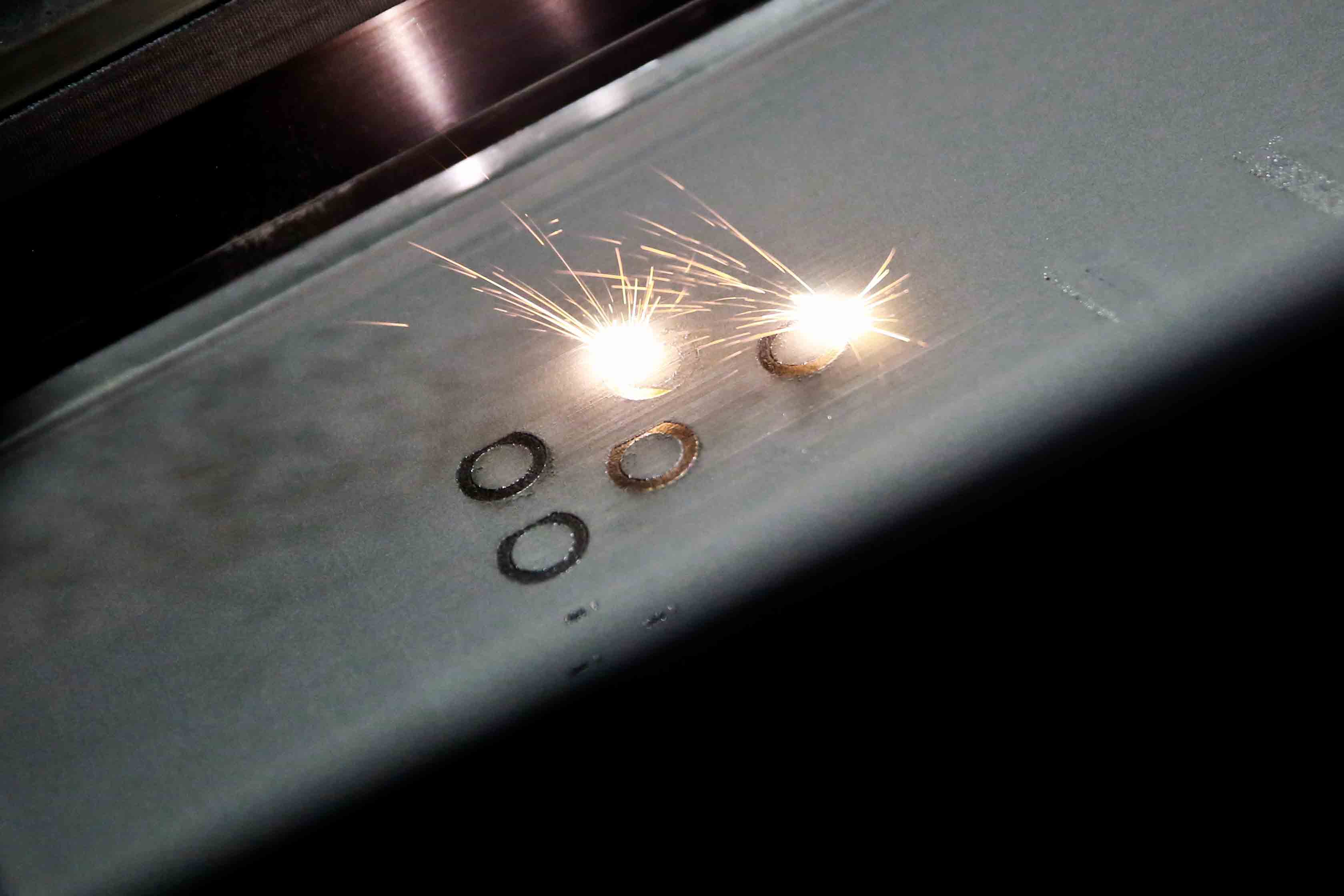

The printing process looks spectacular: Small sparks - similar to a sparkler - flash sporadically over an even, gray surface. Dark-gray seams are left wherever there had been a flash.They won’t be seen for long though: As soon as the sparks stop, a slider distributes a new wafer-thin layer of gray powder evenly onto the surface. And the process starts over again. On areas specified by the control software, the metal powder – usually aluminum, titanium or a titanium-aluminum - alloy - is precisely heated by a laser within one hundredth of a millimeter. The powder melts in these places, hardens, and forms one of thousands of layers of a structure that is often very complex. This process repeats itself for hours.

„Additive Fertigung“ nennen die Spezialisten diese Herstellungsweise. Denn anders als bei der „subtraktiven Fertigung“, wo aus einem Metallblock ein Werkstück herausgesägt oder -gefräst wird und Details abgeschliffen oder gebohrt werden, entsteht hier das Produkt Schicht für Schicht. Der Clou dabei: Was gefertigt werden soll, ist bis ins allerletzte Detail individualisierbar. Weil das nicht erhitzte Pulver im Bearbeitungsraum verbleibt, sieht man das Druckergebnis erst ganz am Ende. Bis das überschüssige Pulver abgebürstet wird, umhüllt es das dreidimensionale Produkt. So, wie Wüstensand ein Autowrack verschwinden lassen kann, bleiben auch die hergestellten Werkstücke zunächst verborgen. Willkommener Nebeneffekt: Das verbliebene Metallpulver kann zu 95 Prozent weiterverwendet werden.