© The Ocean Agency / Gregory Piper

New Approaches to Coral and Biodiversity Conservation

Never heard of the acronym OECMs? Then it's high time you did. It stands for a new instrument for the protection of biodiversity on land and in the sea.

Researchers from the U Bremen Research Alliance want to help establish alternative protected areas – for example in the Coral Triangle off Indonesia.

The sharks and manta rays of Raja Ampat are a real attraction. Divers from all over the world flock to the archipelago in eastern Indonesia to see them in their natural habitat. Together with the local community, a tourist resort has established a sanctuary for the endangered animals, and hunting them is prohibited. For local tourism, the sharks have become an important source of income, while also contributing to ecosystem health and species richness.

“Often, marine protected areas in particular are just a paper tiger. The local population is far too rarely involved in conservation efforts.”

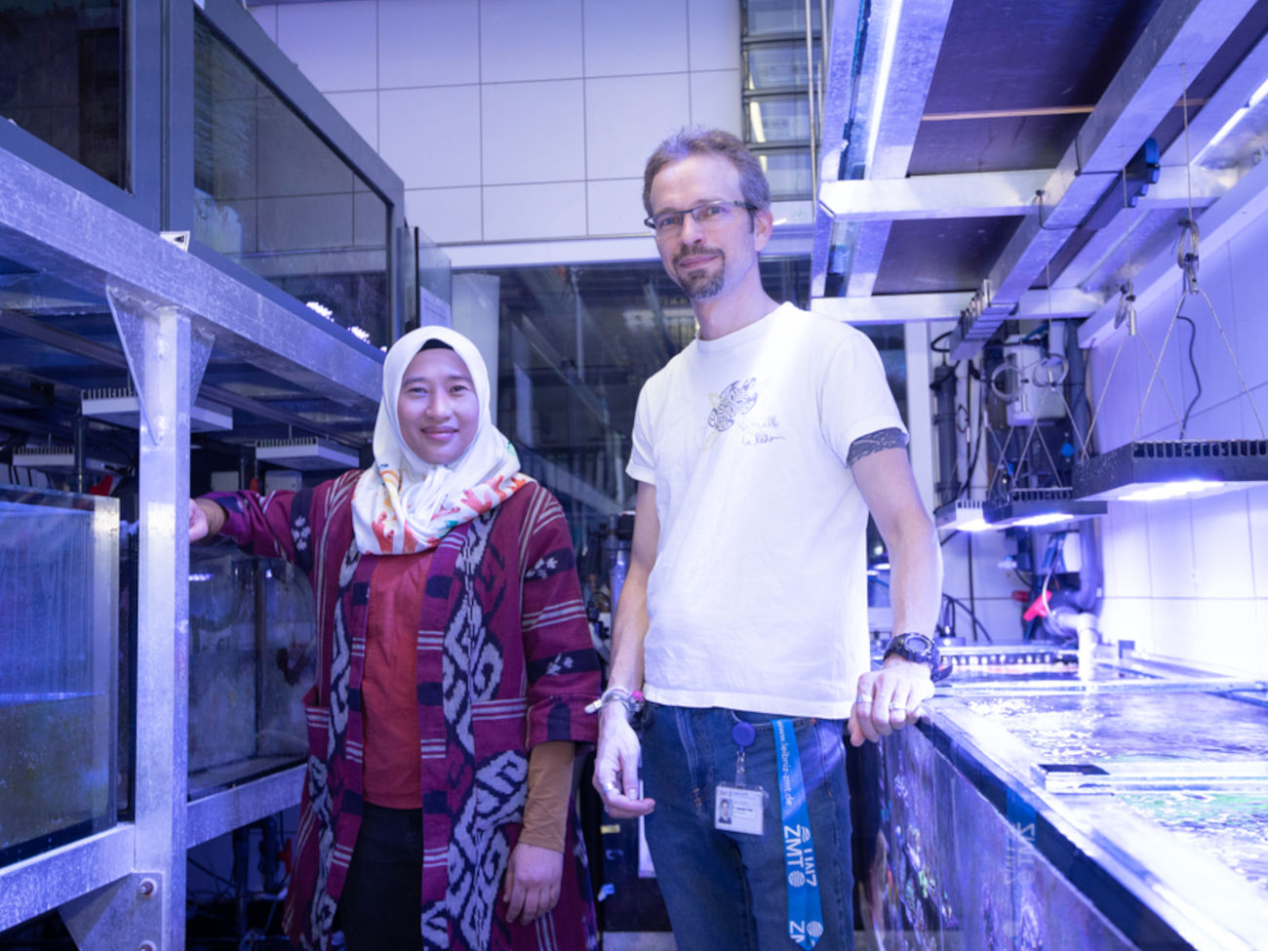

“Raja Ampat is an example of an OECM,” says Estradivari, a doctoral student at the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) and the University of Bremen, both member institutions of the U Bremen Research Alliance. The acronym stands for “Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures.” This refers to areas that are not protected natural areas, but are managed and sustainably cultivated by indigenous people, local communities, or even the private sector. Often this is done in alignment with centuries-old traditions and values.

The global loss of biodiversity is enormous. Researchers estimate that up to 150 species disappear every day. According to the international Red List of Threatened Species, more than 40,000 species are in acute danger of extinction. These include 41 percent of amphibians, 37 percent of sharks and rays, 33 percent of corals, 26 percent of mammals, and 13 percent of birds.

To preserve the diversity of ecosystems, their genetic material, and the richness of species in animals, plants, fungi, and microorganisms, governments have so far mainly relied on the establishment of nature reserves. “They are not enough to stop the loss,” states Dr. Sebastian Ferse, reef ecologist at ZMT. “Often, marine protected areas in particular are just a paper tiger. The local population is far too rarely involved in conservation efforts.”

Furthermore, there are far too few protected areas, and those that do exist are usually too far apart. Thus, an exchange of genetic material is hardly possible. “It’s a huge problem,” Ferse states. After all, evolution requires exchange. Coral larvae, for example, usually have to settle on the seafloor within a week, otherwise they die. To complement nature reserves, the United Nations Biodiversity Conference has brought OECMs into the conversation as an additional conservation concept. According to the ambitious demand, at least 30 percent of the land and sea area should be placed under protection by the year 2030.

© Jens Lehmkühler / U Bremen Research Alliance

OECMs partially differ from nature reserves as conservation is not defined as their primary goal, but is achieved as a side effect of the measures. But which areas are suitable for this? How does one measure the ecological effects? Until now, there has been a lack of mechanisms for identifying, recognizing, and reporting OECMs. An international team of researchers involving the environmental protection organization WWF, ZMT, and the University of Bremen has now developed such mechanisms for the first time, using the example of Indonesia’s coastal waters. Staff from various Indonesian institutions and the Ministry of the Sea were also involved in the preparation of the study.

With its 17,000 islands, the region is one of the areas with the highest marine biodiversity in the world. This is thanks to the corals. The country lies in the Coral Triangle, an area about half the size of the USA that spans Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea. “Coral reefs are not only beautiful and fascinating in their diversity,” Sebastian Ferse enthuses. “With an estimated up to one million species, they are the most species-rich underwater habitat and are enormously important for the material cycle in the sea, as well as for commercial activities such as fishing or tourism. Moreover, they protect coasts from wave energy.”

Yet they are threatened, massively. From fishing, ocean warming and acidification, nutrient inputs, and sewage. Their sustainable protection is therefore all the more important. “In our study, we identified more than 390 areas that qualify as marine OECMs,” marine ecologist Estradivari explains. Among them are shark sanctuaries like the one in Raja Ampat, where nature-friendly tourism is practiced. But above all, there are regions where indigenous communities fish sustainably and manage resources together – in the traditional way known as “Sasi,” as in some areas on the Moluccas.

© Jens Lehmkühler / U Bremen Research Alliance

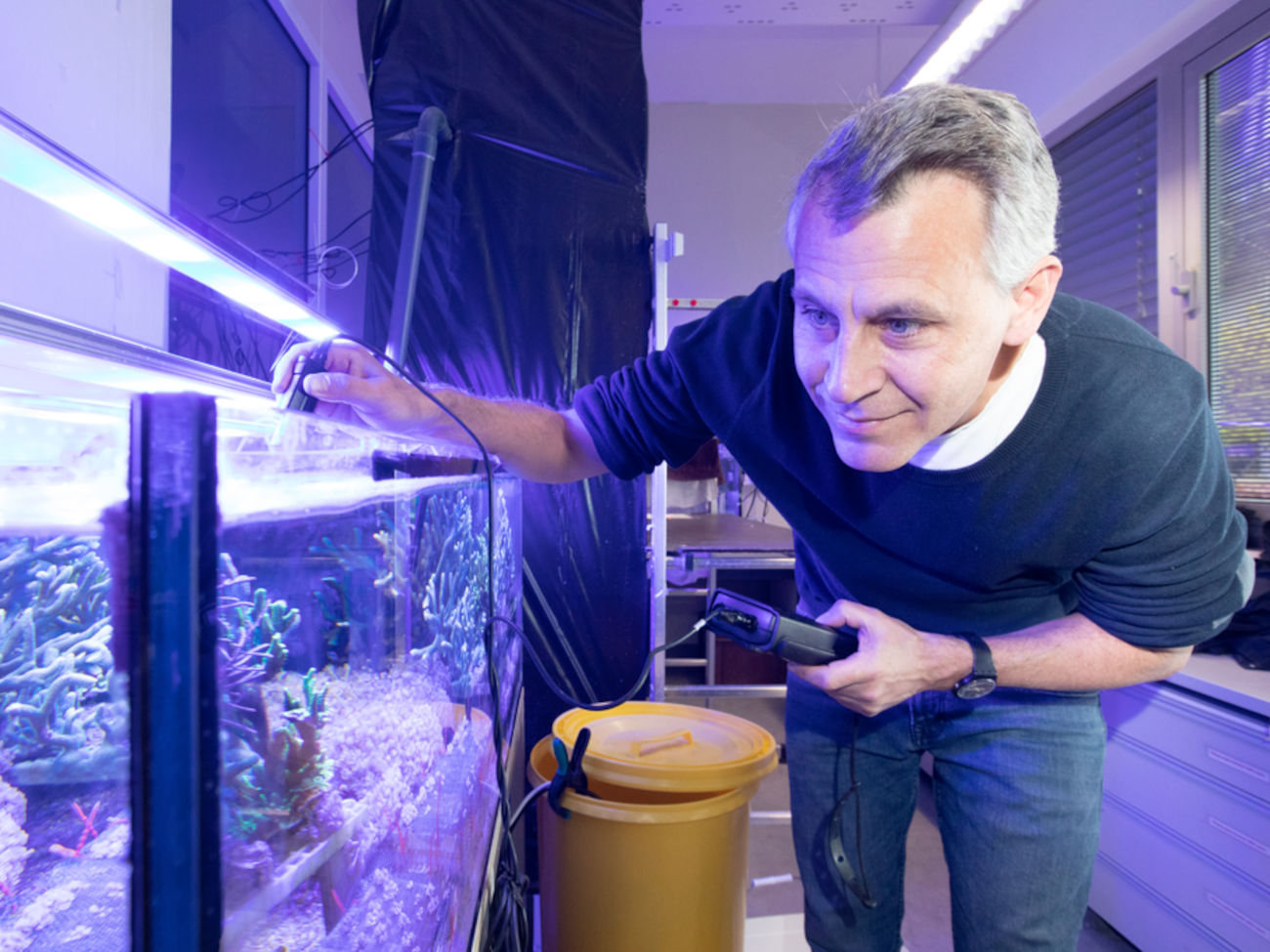

The study is a result of an international research project in which another Bremen resident is significantly involved: Professor Dr. Christian Wild, head of the Department of Marine Ecology at the University of Bremen. “4D-REEF”, as the project is called, investigates the role and potential of reefs in special habitats that are taking up more and more space – turbid coastal waters. Unfiltered sewage from megacities flows into these areas, as does fertilizer from intensive agriculture. “You often can’t see your hand in front of your face in them,” Wild says.

At many sites, this leads to the death of stony corals. Reefs degenerate into rubble deserts, and biodiversity is lost. But at others, corals have adapted to the extreme environmental conditions, proving robust and resilient. “It is quite astonishing,” Wild says. “We want to understand why that is and what we can learn from it for the conservation of corals as a whole. Our textbook knowledge doesn’t get us anywhere here.”

Filamentous algae play a role in this process. Estradivari is investigating their importance in her doctoral thesis, which is being supervised by Christian Wild and Sebastian Ferse. After all, 4D-REEF is also an international educational program. Five universities, two natural history museums, three research institutions, several companies, and the environmental protection organization WWF are among the partners. Filamentous algae and corals are competitors for settlement areas on the seafloor. Algae thrive particularly well in a nutrient-rich, turbid environment. But how the interaction between algae and coral unfolds, and what influence light availability and nutrient concentration have on the competition, is not known. The researchers hope to gain new knowledge in this area as well.

„Bremen offers outstanding opportunities in coral research.”

The cooperation between the Department of Marine Ecology at the University of Bremen and the ZMT is close. “We complement each other quite excellently in our respective areas of expertise,” says the Munich native. “With its partner institutions in the U Bremen Research Alliance, Bremen offers outstanding opportunities in coral and marine research. That’s something the state can be proud of.”

Wild advocates the establishment of OECMs, especially in turbid reefs. “We are in a desperate situation,” the researcher says. “Our coral reefs are doing very, very badly. Probably the worst they’ve ever been in the history of the Earth.”

© Jens Lehmkühler / U Bremen Research Alliance

Traditional research, as well as policy, focuses too much on the “beautiful” reefs in azure waters and neglects the murky habitats, he says. “We need to think and act in a new way,” Wild emphasizes. “OECMs can fill a gap here.” But other conservation tools that incorporate human use, such as biosphere reserves, are no less important a tool for biodiversity conservation, he adds.

The chances of marine OECMS actually being designated as protected areas in Indonesia are not bad. “With our research, we want to support the government and encourage them to take this step,” says Estradivari, who worked for WWF in Indonesia for a long time. To date, less than eight percent of coastal waters in Indonesia have been designated as marine protected areas. The government is currently revising its protection concept.

International Coral Reef Symposium in Bremen

Coral reefs form a habitat that can only be compared in importance to tropical rainforests. They are facing unprecedented threats. Up to 1,000 participants at the 15th International Coral Reef Symposium (ICRS; July 3 to 8, 2022) in Bremen will discuss how this habitat can be preserved. The conference brings together leading scientists, early-career researchers, conservationists, marine experts, policy makers, and the general public. The University of Bremen and the Bremen Convention Bureau are organizing the most important international conference on coral reef science, conservation, and management. Prof. Dr. Christian Wild, head of the Department of Marine Ecology at the University of Bremen, is chairing the conference.

This article comes from Impact – The U Bremen Research Alliance science magazine

The University of Bremen and twelve non-university research institutes financed by the federal government cooperate within the U Bremen Research Alliance. The joint work spans across four high-profile areas and thus from “the deep sea into space.” Biannually, Impact science magazine provides an exciting insight into the effects of cooperative research in Bremen (in German).