© Salsabila Ariadina / Adobe Stock

Out of This World: Philosophy for Another Planet

It is very likely that one day humans will land on Mars. The philosophers Norman Sieroka and Abootaleb Safdari investigate what our lives there might look like.

A lack of oxygen, dangerous space radiation, temperatures as low as -120 degrees Celsius – the living conditions on Mars seem hostile to life. Nevertheless, space agencies and private companies such as SpaceX are competing to send people there. According to NASA, this could happen as early as in the 2030s. But what could human life on Mars look like? Scientists at the University of Bremen are researching this in the Humans on Mars initiative. Among them are Norman Sieroka, professor of theoretical philosophy, and the research assistant Dr. Abootaleb Safdari. “On Mars, we will be vitally dependent on machines, robots, and AI systems,” Sieroka states. What does that mean for our relationship with them?

To answer to this question, Sieroka and Safdari are working closely with other Humans on Mars researchers. The initiative, in which researchers from the natural and engineering sciences cooperate with researchers from the humanities and social sciences, started around two years ago. Some researchers are investigating which creatures need to be bred on Mars in order to produce food, bioplastics, or oxygen. Others are concerned with space radiation: It is harmful to humans, but could it possibly be used as a source of energy as well? Many of these different research approaches are clustered in an application for the Excellence Strategy funding program of the German federal and states governments. The researchers will submit a full proposal for their “The Martian Mindset: A Scarcity-Driven Engineering Paradigm” project in August 2024.

Life on Mars – Between Thought Experiment and Real Perspective

“Cosmology has a long tradition in the history of philosophy,” explains Norman Sieroka. The infinite vastness of the universe and the seemingly perfect orbits of planets already fascinated ancient philosophers such as Aristotle. Another tradition of thought approaches the subject from the opposite direction – not from Earth to space, but from space back to Earth. What do we learn about our life when we look at it from a distance? Space travelers who have seen Earth from space have reported a sublime feeling and a feeling of being connected with all of humanity. Researchers call this altered perception of life on Earth the “overview effect.”

© Patrick Pollmeier / Universität Bremen

The Humans on Mars research group is looking at both aspects: exploring the unknown and seeing the familiar from a different angle. On the one hand, researchers are working on concrete solutions for the highly probable scenario of humans landing on Mars one day. “On the other hand, as philosophers, we use the considerations about life on Mars as a thought experiment,” says Sieroka. Many of the challenges that arise on Mars are also relevant to life on Earth. These include the sustainable use of resources – a topic that is more important to us on Earth than ever before. Sustainability is even more important for life on Mars, as there are no plants, industrial production, or liquid water. Norman Sieroka is certain that it is precisely this pointed, but also unfamiliar perspective that can enrich our discussions.

Robots and AI Systems on Mars – Tools or Colleagues?

It is not only the question of sustainability that is becoming more pressing on Mars, but also that of the relationship between humans and technology – Sieroka and Safdari’s field of research. “Robots and AI systems in particular would be even more vital on Mars than they already are on Earth,” says Safdari. They would be indispensable for many things, among them building habitats for people, extracting water and minerals, and repairing solar panels. They would carry out some of these tasks independently, and some of them would be controlled by humans.

© Bastian Dincher / Universität Bremen

In any case, the cooperation would be closer and even more important than on Earth. More important because it could have life-threatening consequences if systems for generating oxygen, for example, fail. Closer, because it would take up to 20 minutes for a message from Mars to reach Earth. “So if a device doesn’t work, you can’t quickly ask people on Earth for advice,” says Sieroka. The relationship and dependency of humans and technology would therefore be as close as we usually only know from interpersonal relationships. Does that mean that we would perceive robots and AI as colleagues rather than machines?

Interviews on the Trail of the Martian Experience

The scientists are investigating concepts that might shape the relationship between humans and robots. For example, what characterizes trust? What unchangeable elements are part of it? Norman Sieroka illustrates this with a comparison, “A melody can be higher or lower, louder or quieter. But if it contains no sounds, it is no longer a melody.” In a similar way, the philosophers search for the sounds, the basic building blocks of trust.

© Patrick Pollmeier / Universität Bremen

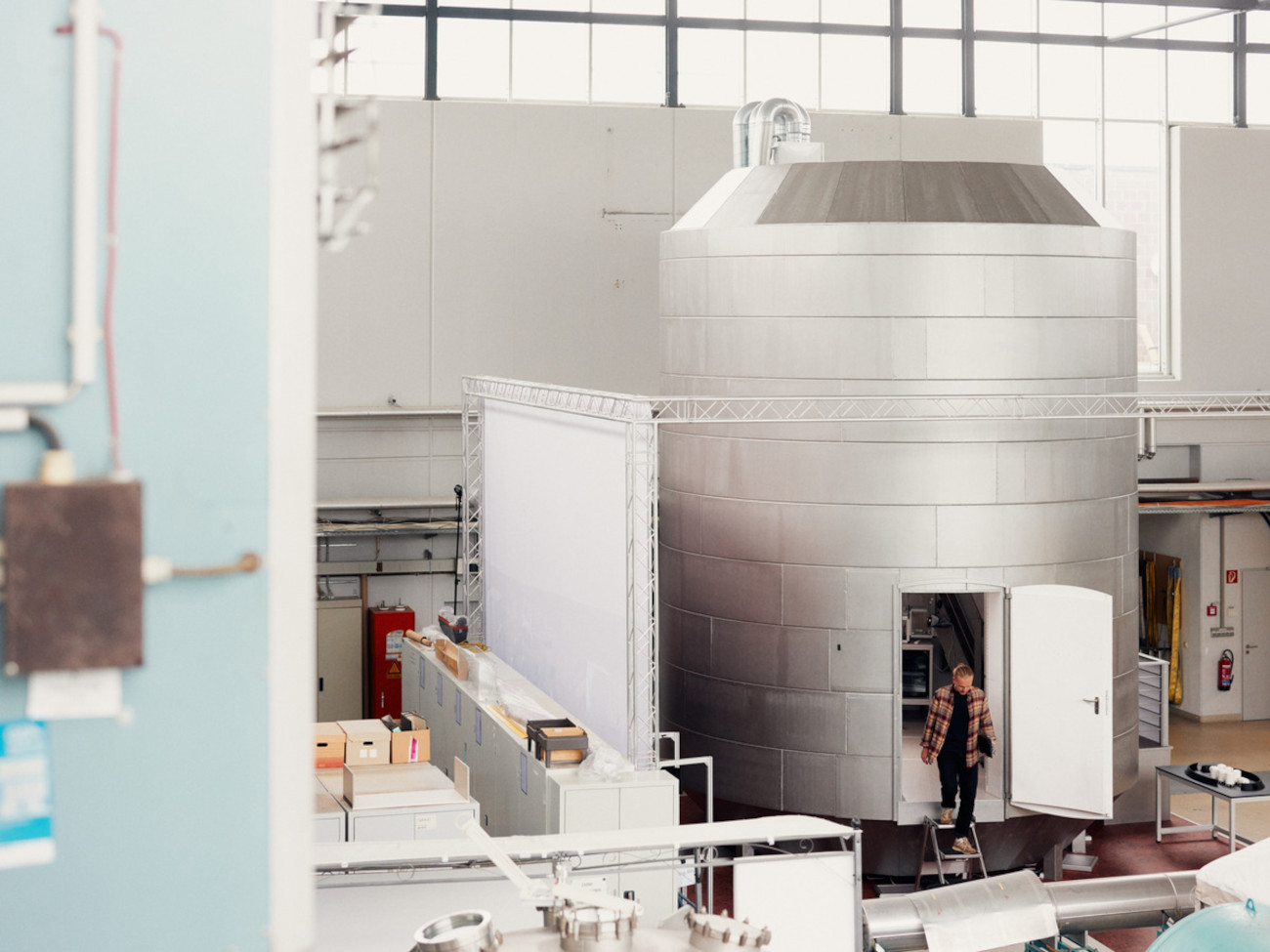

But is trust the right term at all to describe our relationships with robots? In addition to theoretical considerations, Safdari and Sieroka want to investigate this question with the help of micro-phenomenological interviews. They want to use them to find out how people perceive working with machines in situations like the one on Mars. “Of course, we can only approximate such situations,” admits Abootaleb Safdari. Yet, there are ideal facilities for such an approximation at the University of Bremen, precisely at the MaMBA (Moon and Mars Base Analog) at ZARM (Center of Applied Space Technology and Microgravity). It houses a habitat module that could also exist on the Moon or Mars. It consists of several cylinders, each with a diameter of around five meters and a height of six to seven meters, in which researchers test life and work on Mars. From cooperation with robots to delayed communication with people on Earth, the living conditions on Mars are simulated as authentically as possible.

Researchers who have worked here would then be invited to talk to the two philosophers afterwards. They would want to provide the researchers with as few terms and concepts as possible. For example, Sieroka and Safdari would avoid questions like “Did you trust the robot?” “Once the term ‘trust’ is in the air, it is difficult to think in other categories,” explains Sieroka. And that is exactly what the two scientists are interested in: going beyond traditional categories to redefine the relationship between humans, robots, and AI systems.