“The Lobbyists Have Professionalized Themselves”

A study conducted by the University of Bremen reveals why there is little progress in agricultural and environmental policy

Dr. Guido Nischwitz never anticipated this. The Süddeutsche Zeitung had only just published an article about his study, ‘Interrelations and Interests of the German Agricultural Association’ and it wasn’t long until the telephone lines were inundated with calls. Since then, Nischwitz, head of the Department of Regional Development at the Institute for Labor and the Economy (iaw), has become a media star. German broadcasters ARD and ZDF, the TV program die Heute-Show, various radio broadcasters and more than 20 newspapers have reported on the research findings from Bremen. The geographer, together with his colleague Patrick Chojnowski, wrote the controversial 60-page paper on behalf of the German Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU).

Mr. Nischwitz, you and your colleague uncovered interrelations on a large scale. You investigated 93 players and 75 institutions based on publicly accessible information and found out that representatives are also lobbyists and people exerting influence on a large scale are determining the agricultural policy. Was there any criticism here or even threats concerning this?

We worked very thoroughly and honestly and no one questioned our findings. What was interesting was that many of our interview partners from associations, administration and politics certainly didn’t want to be named or quoted in public. At the same time, officials with multiple roles from the agricultural and food industry and the agricultural business, who we revealed in the study, made themselves scarce. They didn’t want to publicly say anything about their many roles and the conflict of interests resulting from this. We received many positive calls at the institute particularly from small and mid-sized farming enterprises that praised the fact that someone had, at long last, finally said something. Ninety percent of agricultural enterprises are, after all, members of the German Farmers’ Association (DBV) or the regional associations. According to a current forsa (German market research institute) survey, more than half feel that they are being poorly represented here but are unable to get out of the system. In the villages and regions there is often social pressure to belong to the DBV which also offers a comprehensive service package. It is a little like the AA for farmers.

Can you briefly outline the problems that German agriculture faces and which initiated the study?

Biodiversity, water and air quality, the climate and animal welfare are all under threat. Everyone will be familiar with the current debates: nitrate contamination of the groundwater, use of glyphosate, insects dying out. At the same time, it is the small and mid-sized farming enterprises that are suffering from the consequences of the transformation in agricultural structures. Up until now, the German and European agricultural and environmental policy has hardly made any progress in solving urgent problems. The joint agricultural policy of the EU (GAP) represents almost 40 percent of the EU’s budget; it is the biggest budget item. Approximately 408 billion euros are being allocated between 2014 and 2020. Yet many attempts to couple the direct payments for the agricultural enterprises more strongly with effective environmental and animal protection requirements have been defused again and again. There is the accusation that the necessary reforms and adaptations are being systematically weakened or prevented by lobbyists. With our study, we wanted to ensure more transparency in the political decision-making process and follow-up any indications and signs of influence being exerted.

“There is the accusation that the necessary reforms and adaptations are being systematically weakened or prevented by lobbyists.”

But this problem has already been known for a long time?

Yes, that’s exactly it. The negative impact of the intensification in agriculture has been criticized by the Advisory Council on the Environment, amongst others, since the 1980s, and the negative effects this has on humans, nature and the environment have been described. We already presented this in a similar study at the turn of the century. What has happened in the meantime? Not that much really but we have seen that the lobbyists have skillfully professionalized themselves further.

Can you give a few examples?

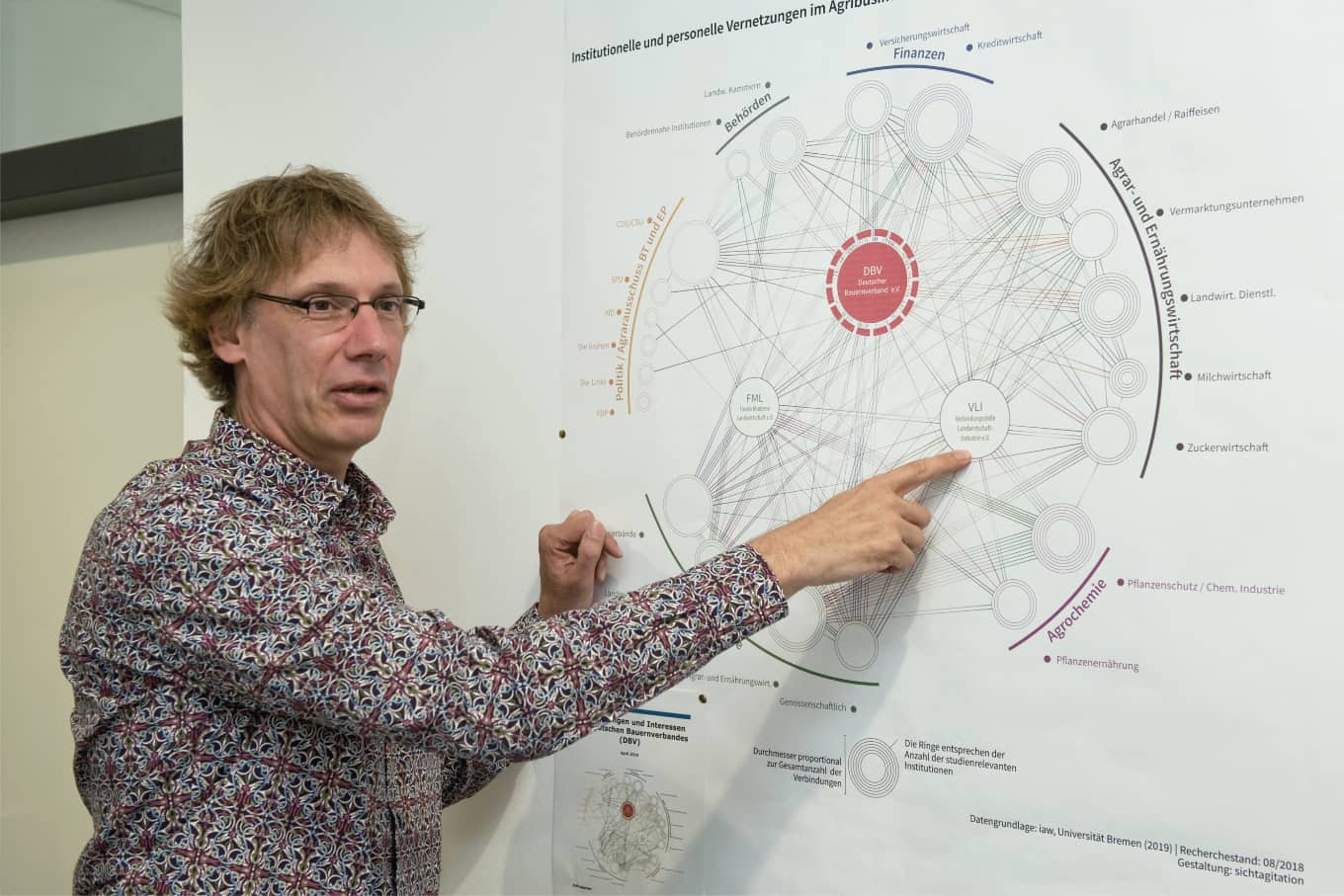

We took a closer look at the institutional and personal interrelations between politics, the financial world, the agricultural and food industry, agrochemical businesses as well as authorities and associations. In doing so, we identified around 560 interrelations, which we visualized with graphics. The focus was on ascertaining the managerial figures in supervisory committees and management boards which are relevant nationwide. What was noticeable here was that there are up to ten functionaries with various multiple roles with key positions in politics, associations and industry and they are usually closely associated with the DBV. They include its chairman Joachim Rukwied, who has at least 18 prominent positions and CDU parliament member and president of the Agricultural Association of Westphalia and Lippe, Johannes Röring, who has 15 positions. They are always included in important political decision-making processes. With the many different roles, you never know what their current function is.

Besides the ties between individual agricultural functionaries and the relevant interest-led companies, you also revealed various interfaces in your study that skillfully exert an influence on the public or offer a platform for the coordination of industry and agriculture.

Yes, it was particularly interesting that we were able to reveal these network hubs. These include the Liaison Office for Agriculture and Industry (Verbindungsstelle Landwirtschaft-Industrie e.V.), a platform which explicitly brings together management from the finance industry, agricultural trade, the agricultural-chemical field and the farmers’ association as well as the Forum of Modern Agriculture (Forum Modern e Landwirtschaft) which is, in its own words, a powerful institution in PR for creating a positive image of the agricultural industry. We assume that both associations not only exert an influence on sociopolitical debates but that they also want to influence political policy and decision-making processes.

But doesn’t the consumer have a significant say in things? There is, for example, particularly now, a greater public focus on climate protection – could pressure increase from this side and could ecologically produced products have an edge?

The social pressure for change in farming will increase although this also needs to be seen in consumer behavior in the stores. As long as people think that a pound of mince costs 2 euros at the most, nothing will change. Groceries in Germany have to offer value for money.

Your study ends with concrete recommendations for action. You not only demand a transparent lobby register of politicians in federal parliament but also the documentation of the “legislative footprint”. What is this?

I can explain this with an example: There is an ambitious proposal for a nationwide fertilizer ordinance to counter the nitrate contamination of our groundwater due to the entry of too much nitrogen-liquid manure. During many years of debates concerning this ordinance, a legislative package is finally passed in the federal parliament – far too late – which, according to experts, only exacerbates the nitrate problem instead of solving it. The EU Commission intervenes, yet again, and demands clear improvements. Why? When did someone speak to a parliament member and discuss this ordinance in the German federal government-federal state negotiations and influence this? And who exactly was involved? The “legislative footprint” should clarify this.

What would you like to see in the future?

I hope that we will succeed in restricting the influence of the farming lobby on the legislative processes and political fields as well as the environmental and rural development policy and finally tackle the problems that have already been known for decades.

Profile:

Dr. Guido Nischwitz (57 years old) has been a research associate at the Institute for Labor and the Economy (iaw) of the University of Bremen since 2004 and is currently researching the topics regional and rural development policy, productive towns, regional public services as well as regional governance. Nischwitz was born in Bonn, studied geography at the University of Bonn, and did his PhD at the University of Vechta. He was also a research associate and head of research at the Institute for Ecological Economy Research IÖW for several years. Guido Nischwitz lives with his partner and has three children.