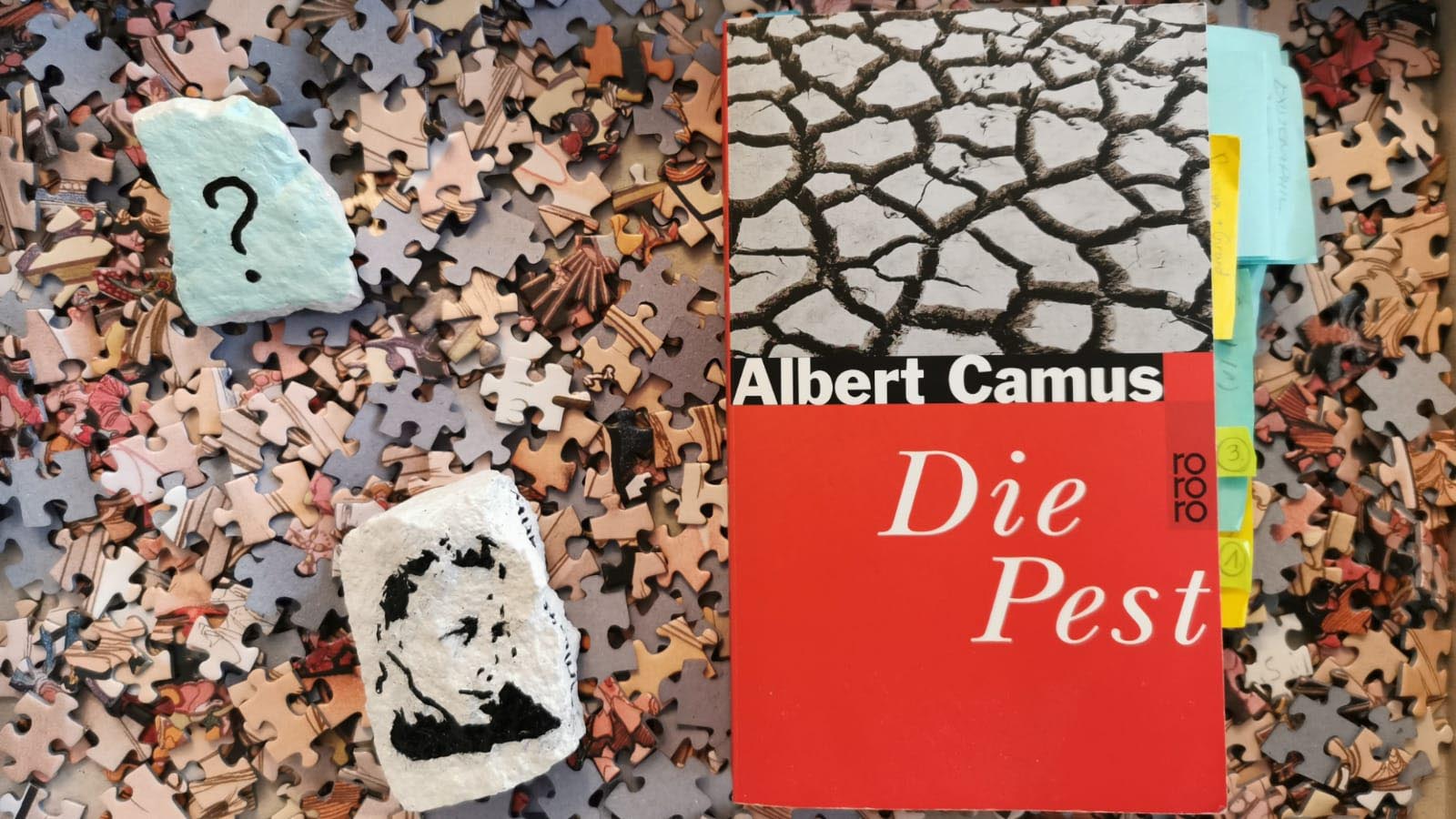

© Svantje Guinebert

The University of Bremen Reader Albert Camus’ "The Plague"

The world literature classic is at the core of a diverse project.

Teaching staff and students at the Institutes of Philosophy, Anthropology and Cultural Research, Romance Studies, and Political Science at the University of Bremen have developed the project “Questioning Solidarity: The University Reads Albert Camus’ The Plague (1974)” (Solidarität neu befragen: Die Universität liest Albert Camus’ Die Pest (1947).” The project is being funded as part of the “One Uni – One Book” program and has the aim of motivating as many interested people as possible to read and think about this classic of world literature this year. In debates, classes, an exhibition, and further formats, the focus will be on addressing the connections between Camus’ work and current issues of solidarity from various perspectives. The “Solidarität neu befragen” blog summarizes the diverse initiatives and thoughts. up2date. is bringing this guest article from Dr. Svantje Guineberg (Institute of Philosophy) to you to get you ready for the events that will take place.

And Afterwards?

“And, indeed, as he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

These are the closing words from Camus’ The Plague. We can – and should – also ask ourselves what the end of the current so-called corona crisis might look like, what the long-term consequences might be, and what consequences we want to draw from it as individuals, as a society, and as a world community. For the crisis opens our eyes to necessities and fundamental issues, including and especially to those that a (partially) affluent society can displace over the long term. Other deeply unsolidary, marginalizing, and unjust situations, which were already apparent before the corona pandemic, call for a clear, unexcited, philanthropic view in order to constantly and concretely try to work for the better.

Solidarity – Concrete and Committed

Camus is about solidarity, concrete and committed. Applied to our present, this would mean solidarity even beyond the crisis. As a society, we must ask ourselves, for example: In which areas do optimization efforts and benefit calculations make sense, in which contexts are other forms of practical rationality more appropriate? Which possibilities of social and individual lifestyle do we want to look at, promote, invent – now that it has become clear that obviously much more is possible than it might usually seem in general? It is not enough to focus solely on injustices and problems – we should hold on to what can be learned from current experience as an insight into what is good. When it is said that there are some positive aspects of this challenging time, “deceleration” is often referred to. To what extent can and should deceleration be maintained? Who are those who can help to maintain it? What needs to be decelerated and what are the areas in which rapid and expeditious action is necessary to make deceleration possible and fair?

© Svantje Guinebert

Reclaiming Earlier Freedom

It is remarkable how many restrictions and how much behavioral change our society is prepared to make when it comes to combating the spread of a virus. Many people ask why conversions and losses of such magnitude did not seem possible in view of the climate catastrophe and the suffering of refugees – it will become more difficult in future to invoke customary rights and lack of alternatives. Impressive and enduring could also be the impression of how suddenly what was considered safe dissolves and how quickly freedom can be limited. Which liberties will be curtailed in the course of the fight against corona, which are inviolable, and which will have to be won back afterwards? After the crisis, regaining freedom that were once taken for granted may be difficult – especially in light of past experiences of calls for a more regulatory state. Which forms of regulation are compatible with solidarity and freedom, which are necessary, which are unjust, dispensable, dangerous, harmful? And what if the call for strength, perhaps even for strong political figures, due to worries and fears becomes strong after the crisis?

Preventing the Resurgence of the Plague

At the latest after the worst has passed, when the virus has been successfully combated or at least its effects have been mitigated, it is important to reflect on what has happened as well as on what is to come. Existential needs, fears, and difficulties can have the effect of giving impetus to parties, ideologies, and positions calling for the abolition of the rule of law and the welfare state. How can we prevent injustice and poverty from becoming as bad or worse after the crisis than before? Camus uses the term plague to describe the Nazi occupation of France and the events of the Second World War; for us it is important to prevent a resurgence of this or similar forms of plague on the back of the spread of the coronavirus.

So, after Pest and Corona, what can it mean to preserve the good and prevent the bad? What opportunities and responsibilities do academics and universities have to participate in this?

In other words: How can a return of the plague “for the bane and the enlightening of men” – be it in the form of a virus or an inhuman ideology – be prevented and fought in a philanthropic and supportive way?

Links:

Podcast “Studentische Blick in das Buch und darüber hinaus”(in German only)

Podcast „42 und so“ (in German only)