© Privat

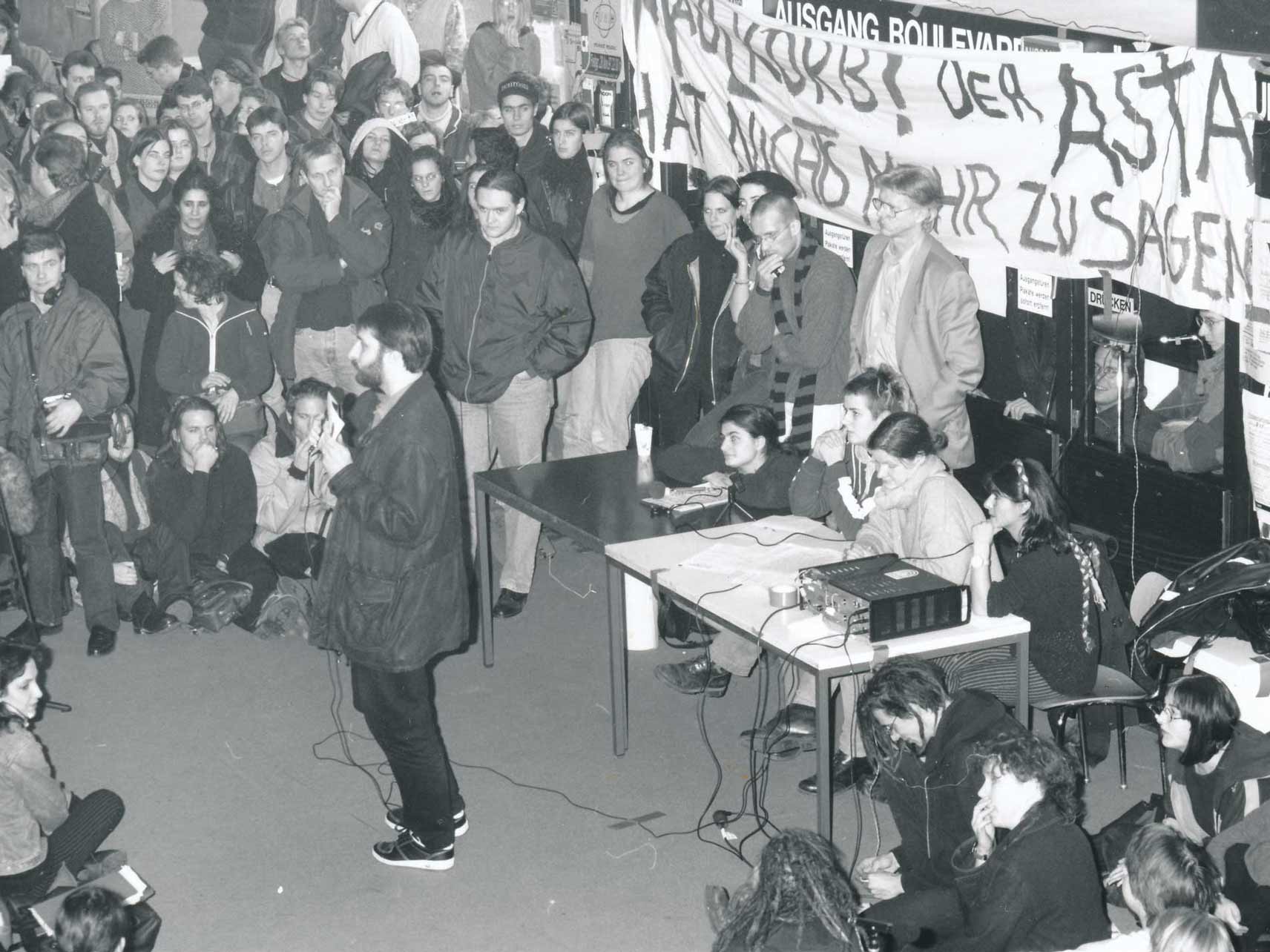

“Those Who Wanted, Could”

The well-known economic scientist and professor Rudolf Hickel was part of the founding generation at the University of Bremen.

The former professor looks back and is amazed but also critical of the beginnings of the reform university and where it is now in comparison to back then. Hickel is one of four guests who will talk about the founding era during the online talk held by the University of Bremen and the Alumni Association at Radio Bremen on the evening of January 20. It is the last event of the “Just Change the World” series marking the University of Bremen’s 50th birthday.

Mr. Hickel, with what expectations did you take on the role of professor at the University of Bremen in 1971?

I came to Bremen with enthusiasm to contribute to a modern reform university.

Which university did you leave at the time?

I initially found my feet at the great yet very traditional University of Tübingen as a student and then scientific assistant. The university was characterized by the governance by professors. I then went on to work as an assistant in Constance. The University of Konstanz was also newly established but they went down an entirely different path to the one taken in Bremen. I wanted to go to a university that was truly undertaking reforms.

“If we would have had to accredit it back then, the university would have never been established as it was.”

What was the beginning phase like in Bremen?

We wrote entirely new degree regulations and diploma examination regulations that were marked by the new spirit: interdisciplinary studies. Thus, a combination of many subject fields. The IES - Integrated Social Science Introductory Degree - stood for that at the time. The second aspect that was very important was the practical orientation. For me, this mainly meant strengthening career orientation in the societal context. We wanted to bridge the gap between studying and practical relevance in Bremen and we were successful in doing so.

In today’s world of degree accreditation, it would not even be thinkable to start with teaching and studying before there are even study and exam regulations.

If we would have had to accredit it back then, the university would have never been established as it was. It is logical - after all, we wanted a reform model. It was also a great opportunity. Back then, there were still innovation opportunities from the bottom up, thus with students and professors who were interested in creating something new. We also received a great deal of rejection and even hatred for this radical reform approach. The rejection was especially immense in my discipline - economics. I always thought about how professors with whom I used to be friends, no longer wanted to be seen with me at conferences. Evidently, there was fear and worry that this young university would deconstruct the model of the old university. Bremen was defamed as a revolution university without any mention of the positive aspects.

“But we were never a commie training center.”

But the critical, sometimes hostile outside world did not necessarily lead to a stronger sense of unity in Bremen. Not everyone was in agreement at the uni either.

In my faculty and in many others, there was never this sense of unity - a left-wing togetherness. Rather, there were the worst types of disagreements right from the beginning, for example concerning the question: what role does the economy play in the state? We formed a varied, colorful world with commie accents. But we were never a commie training center. That was nonsense that caused us to suffer a lot. If you think about what commie training center means, for example in the Soviet Union and authoritarian states, you could say it is total rubbish. That was simply a defamatory statement.

“For me, the most important way of checking my work was asking: how are the graduates doing?”

But there was also another side, something I am a little proud of: the University of Bremen was open-minded and pluralistic but also quarrelsome back then. A great deal was difficult. I, myself, received great criticism within left-wing training parties. But the fact that Conrad Naber, a successful businessman from the region, came to the University of Bremen aged 50, studied economics, and then completed his studies with a diploma thesis - that was a piece of reality. Those who wanted, could. It is often said that all of the left-wing students from the whole republic traveled here. Which is true. There were numerous students who were frustrated at other universities. Yet the majority had grown up in Bremen. They had gone through it all but they were never left-wing revolutionaries.

For me, the most important way of checking my work was asking: how are the graduates doing?” There are some fantastic stories of students who left the uni and went on to great success. There is one significant characteristic of our degrees, namely being “forced” to develop arguments in free speech and dialog. That is quirk that you learnt in Bremen. It was only possible to pick it up because everything was so close and direct between the students and professors. That is something that supported later practical work and we passed it on well.

© Eva-Maria Kuhlke/Universität Bremen

What remains of the reform university and what is still important today?

We nearly always speak litany-like of three criteria: Interdisciplinarity, practical orientation, and one-third parity. If I think about how I, as an economist, formed the first four semesters together with Ulrich K. Preuss, a great constitutionalist, and social scientists - it was amazing. This type of interdisciplinarity is not possible today.

The university is doing well today in terms of being practically oriented. One thing that has been lost since the founding phase is that practical does not only mean practical in a career sense. Practical does not only mean that I know how to optimize accounting in a company later in life. Practical also means paying attention to societal conditions. It was a goal that companies be seen as social entities.

“If you compare the university of 1971 with today’s, it has certainly gained something with the institute establishments and collaborative research centers.”

One-third parity has entirely disappeared. Today, we have a university constitution that is comparable to all other universities. We introduced one-third parity in order to break with the authoritarian rule of the professors, as we put it back then. I believe that the quality of interaction with students and staff is greatly determined by the character of a professor. There are few institutional conditions for this and that is a shame.

If you compare the university of 1971 with today’s, it has certainly gained something with the institute establishments and collaborative research centers. In the founding phase, we were scared that the old professorial rule would return with the institutes. That was a mistake, one that I also made, that has been corrected. Today, those institutes are top-level.

“There is great pressure to fit in thanks to international criteria, standards, and rankings.”

And one last comment, which is a unpleasant but needs to be said: Today, we still have a long-standing dominance of administration over professors. The administration plays a far larger role in Bremen than it does at other universities. That was a founding mistake that we did not notice. The body of professors was scattered. They were different to “normal” professors in their lifestyle. They were especially not obsessed with power. And this created a power vacuum that the administration then filled. Today, the question should be asked: what autonomous decision-making power do the faculties and institutes have in comparison to the administration?

In hindsight, there is great pressure to fit in thanks to international criteria, standards, and rankings, which I can see. However, the university should have used the available leeway more. Despite this, in my opinion, the university is very successful in research and teaching – and exemplary on the international landscape.

Information on the Online Talk on January 20:

The online talk will take place in the 3nach9 TV studio between 6 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. on January 20, 2022, and will be shown live in German English on YouTube. Four guests will discuss the University of Bremen’s beginnings under the title “How it all began …”. You can find out who will be taking part alongside Rudolf Hickel and how you can register on the University of Bremen website.