Bremen: Science since 1610

In 2021, the University of Bremen will celebrate its 50th anniversary. This makes the university one of the younger universities in Germany. Yet the hanseatic city does, in fact, have a long scientific tradition. We followed the trail for up2date.

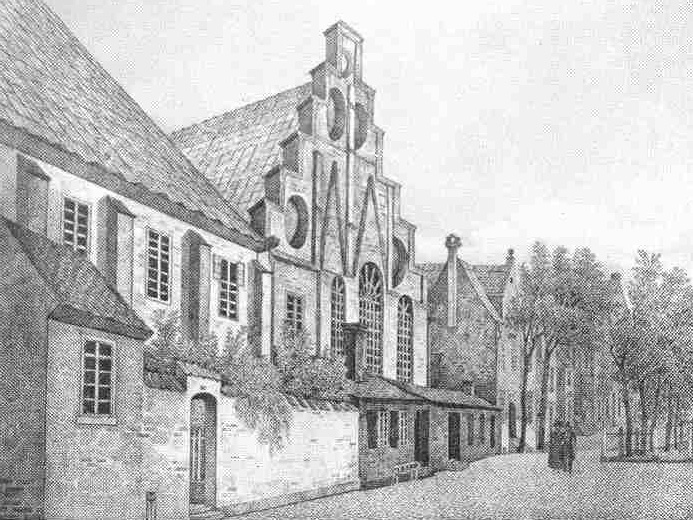

In the center of the city in the St. Catherine’s Monastery courtyard: At the edge of the shopping arcade, framed by two carpark columns, one can find an ocher-colored brick building with lancet windows. These are the remains of the first university in Bremen. Where “Stadtwirt” served schnitzel and tarte flambee until recently is actually where a hunger for knowledge was fed in the early modern era and the foundations for Bremen’s scientific community were laid.

“There was no real university in Bremen before 1971,” says historian Dr. Maria Hermes-Wladarsch at the beginning of our conversation. She is the head of the Department of Historical Collections, Manuscripts and Rarities at the Bremen State and University Library (SuUB). But there were repeatedly the beginnings of a university or a university-like institution. “Firstly, in 1528, the council founded a Latin school. This was the result of the Reformation in Bremen.” As in the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, people turned their backs on Catholicism in the 16th century and followed the teachings of the reformer Martin Luther. The change of confession of a city held the consequence that there were radical changes in the educational sector. According to Luther’s teachings, the church was not to be responsible for upbringing and education, but rather the state. “The former Dominican St. Catherine’s Monastery was named as the location for the new Schola Bremensis.

The Bremen gymnasium illustre was very popular

“The Latin school changed into a university-like institute of academic standard in 1610,” emphasizes the historian. One differentiated between the primary school – paedagogium – and the higher education institute – gymnasium illustre. The gymnasium illustre had four faculties that were typical for a university in the early modern era: theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and philosophy and philology. Based on a Calvinist view, mainly future public officials, such as lawyers, doctors, and council members, were trained there. “The most apparent difference to a university was that the gymnasium illustre could not award academic titles. Only the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation held this privilege.”

The Bremen gymnasium illustre was very popular and flourished in the 17th century, as Hermes-Wladarsch describes. A repeated change in confession of the city was advantageous for the school. “After Bremen had turned away from Lutheranism and took on Calvinism in the 16th century, it became isolated within the Lutheran surroundings and had one of the only Calvinist higher education institutes in Germany. Said institute was, however, part of the European Calvinist education system.”

Pupils came from the city, the empire and from abroad

The pupils not only came from the city and the empire but also from abroad – especially the Netherlands. A typical student in the 17th century was Peter Baumann. His studies can be reconstructed using his album amicorum – a type of album of verses, in which professors, other students and friends could write inscriptions. Born in the County of Moers on the Lower Rhine, he initially studied theology and Hebrew in Bremen until 1644. He subsequently transferred to the University of Groningen. In the autumn of 1648, Baumann, a suitor for the role of preacher, returned to his hometown. He most probably did this with the intention of working as a preacher in one of the many parishes there.

From 1700, the gymnasium illustre attracted an ever-decreasing number of students. “In the frame of the Enlightenment, a denominationally-oriented education lost its appeal,” according to the historian. In 1810, the period of French occupation in Bremen, the gymnasium illustre was closed.

From the monastery courtyard, the trail runs through St. Catherine’s Passage and over Cathedral Court to the cathedral. Here, in the chapterhouse south of the cathedral, is where the Lutheran counterpart of the Calvinistic school was located: The Lutheran Cathedral School.

“The lessons in the gymnasium illustre were Calvinist oriented,” explains Hermes-Wladarsch. Therefore, in 1642, the evangelical-Lutheran archbishop of Bremen founded a school together with the cathedral chapter against the wishes of the council. In 1681, the school became affiliated with the athenaeum, an academic, upper secondary school. However, the school was never able to attain the position or importance of the gymnasium illustre.

From Cathedral Courtyard the trail leads us along the monastery courtyard and into the Knochenhauerstrasse (Knochenhauer Street), where the butchers lived and worked in the Middle Ages and the early modern era. The street leads to Spitzenkiel (street).

Regardless of whether Calvinist or Lutheran, women and girls were not allowed to go to schools and universities. “A possible elementary education, such as reading, writing, and arithmetic, was undertaken at home or in private schoolhouses. A state-run secondary school education was practically unavailable for women,” says Hermes-Wladarsch. Girls’ secondary schools, upper class girls’ schools, or boarding schools were dependent on private initiatives. The main aim of these schools was to turn the girls into good wives, mothers and homemakers.

“That was not enough for the Bremen pedagogy scholar Betty Gleim. For the autodidact, education was the key to enabling girls and women to lead free, autonomous, and independent lives,” states the historian. Influenced by Pestalozzi’s progressive education, Betty Gleim wrote educational history in 1806 when she opened a “School for Upper Class Girls” (Schule für die Töcher der höheren Stände). The school on Spitzenkiel, which at times had four classes and 80 pupils, was managed by Betty Gleim for ten years. In 1809, the “Newspaper for the elegant world” (Zeitung für die elegante Welt) wrote that Gleim teaches “with a familiarity with new proposals, ideas, and aids, in accordance with Pestalozzi’s methods in a light, thorough, and successful manner.”

Less education and more vocational training

Bremen: a scientific and trade city? Around the year 1800, it became increasingly clear that the prioritization of the Bremen middle class was placed on the merchant ideal, which was seen as being important and significant for the community. “The founding of a navigation school in 1798 as the nucleus of the nautical school had the aim of providing structured vocational training for the people in Bremen and those who were so important for the city,” explains Hermes-Wladarsch. Mayor Johann Smidt (1773-1857), who was himself an academic and professor at the gymnasium illustre, said in 1844: “In a trade town where the promotion of material interest must take the foreground, one can only speak of exchange of scientific aspirations within individual circles.” Less education and more vocational training. That is what the traders desired. Hermes-Wladarsch: “With the exception of theology, the academic vocational training placed a focus on practical application: thus, natural sciences, jurisprudence, and medicine.”

Science and education disappeared further and further into private realms and were practiced in associations and groups, such as reading clubs, which were organized by the middle class.

In 1947, the establishment of a university in Bremen became a topic of discussion once more. The university was to communicate the values of the young post-war democracy and in terms of academia, be of a new type. Nonetheless, the academic history of Bremen played a role in the contemporary ideas: “We are dealing with the remains of the old St. Catherine’s Monastery, a place, which in the Middle Ages played a very important role in the clerical and cultural life of our city when the gymnasium illustre, Bremen’s university-like institute, found housing in the old buildings there” wrote hobby historian Johan Hinrich Prüser, brother of the national archives manager Friedrich Prüser, in 1949 in a reader’s letter to the Weser Kurier newspaper. Prüser urged that the opportunity to “connect the establishment of the new university, also spatially, with the honorable tradition of the old school” not be missed. A good 24 years passed until the University of Bremen was founded. Between new starts, setbacks, and the commitment to being the “Bremen Reform Uni”, the academic history no longer played a significant role.