© Titinun Nuntapramote

“I Didn’t Choose Germany - Germany Chose Me”

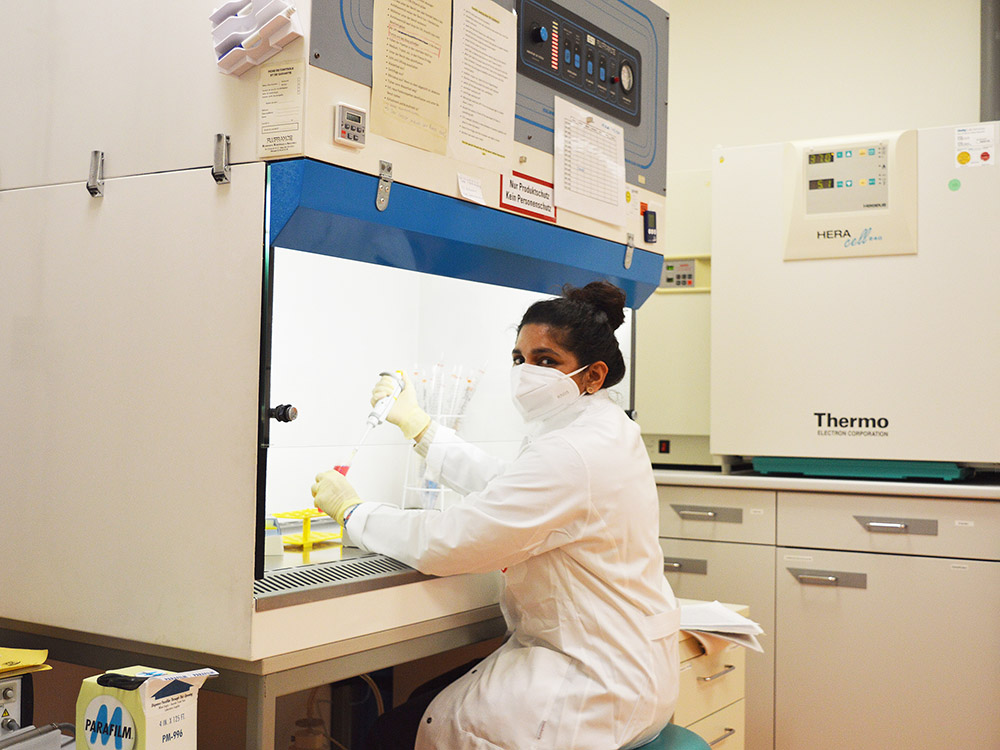

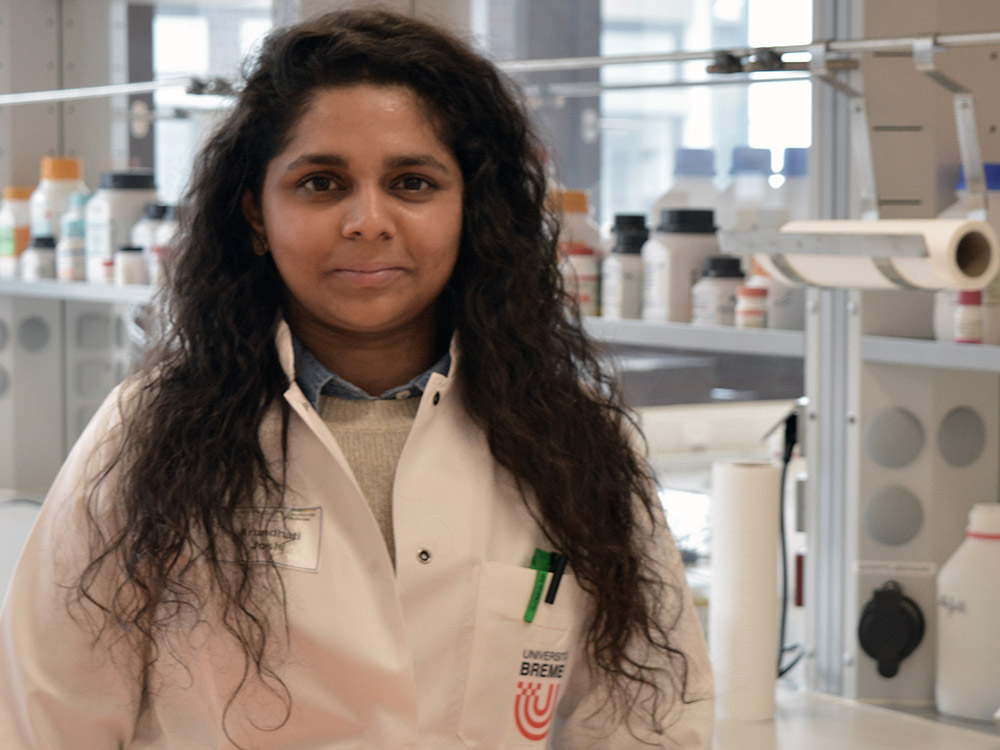

The academic mid-level sector in focus: Dr. Arundhati Joshi from the Institute for Biophysics

Bremen is rather a small place and usually unknown to most of the millions of citizens of the Indian city Pune. However, thanks to the Bremen Town Musicians, which were covered in her German lessons – as is often the case, Arundhati was familiar with the hanseatic city when she came here in 2013. Today, the 29-year-old works as a post-doctoral researcher in Professor Dorothea Brüggemann’s working group at the Institute for Biophysics.

Those who know a little about the international relations of the hanseatic city of Bremen know: The Indian city of Pune has been a partner town since 1976. Yet Arundhati Joshi knew nothing of this when she started her bachelor’s degree in natural sciences in the 4-million-inhabitant city in Maharashtra state in 2010. Much like the English system, in India the transfer from school to university is far more interconnected than it is in Germany. Thus, after graduating from school, she went straight on to complete her bachelor’s degree at a college. “The college had a cooperation with the University of Pune - that is why my degree is from the University of Pune.”

She decided on science instead of the arts when choosing her school subjects: “Nature, plants, animals. Those were the things that had always interested me. I also went on different ‘nature experience trips’ with various organizations during my school training and degree - that was always really interesting,” she states when talking about this part of her youth. She initially did not have to specialize in any particular field for her bachelor’s degree in science and therefore got to know a great deal from the whole spectrum of natural sciences. It was only in the third year that she had to find her focus. “I had already discovered biochemistry and microbiology by that point. Working with bacteria and viruses on a microscopically small level is something that I am increasingly interested in and the related laboratory work is far more than attractive than it is for chemistry, for example!”

© Titinun Nuntapramote

Test for Bremen Completed in India

Whilst she was working on her final exam for the Bachelor of Microbiology degree, she found out that at the University of Pune it was possible to take the placement examination for the master’s degree in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Bremen, which is 6,700 km away. “You have to apply online first and then take the test,” she explains. After having carried out research on the English-language master’s degree - “I had to find out what it was about and what I would be taught” - she applied before even finishing her bachelor’s studies. “And I was accepted directly after successfully completing the exam,” she remembers.

Thus, her path took her Germany. Bremen to put it more precisely. Which is where the previously mentioned Bremen Town Musicians come into play. Arundhati Joshi had chosen German as a foreign language as a subject at her Indian school and that is where the Town Musicians were mentioned – thus, she was already familiar with the hanseatic city. “It could have turned out to be a different country and a different town but the offer was simply great and suited me so well at that moment in time that one could say: I didn’t choose Germany - Germany chose me,” she laughs.

“I was able do far more intensive practical work in the lab here.”

She started her studies at the Bremen uni in the winter semester 2013/14 and really enjoyed her master’s degree: “I already had laboratory experience yet it was only a little in comparison to what was possible in Bremen. I was able do far more intensive practical work in the lab here.” For her master’s thesis, she chose a project in the Neurobiochemistry working group led by Professor Ralf Dringen. The project focused on interdisciplinary research at the interface between brain cells and nanoparticles. “I found it extremely interesting as it dealt with two fields that usually don’t have a great deal to do with each other. I was then able to successfully publish my master’s thesis results,” she reminisces.

PhD Thesis Written at Graduate School

At the end of the master’s degree, the opportunity to gain further qualifications suddenly arose at an interdisciplinary graduate school. Arundhati Joshi went on to write her doctoral thesis on nanoparticles and brain cells there. “To be specific, my work dealt with investigations of if and how it is possible to kill brain tumors with nanoparticles,” states the Indian woman. Working with cell structures, nanoparticles - some of which she had created herself, and chemical matters brought her great joy and led to her attaining her PhD in December 2019. The 29-year-old was also active in the field of teaching. She supervised students during their practical biochemistry sessions and at the same time, she was able to improve her German - which is now excellent.

It was at this point at the latest that it became clear that Arundhati Joshi would embark on a scientific career. This also means one thing for early-career researchers: Keeping eyes and ears peeled in the search for the next job. “It was via the ‘office grapevine’ that I heard that Professor Dorothea Brüggemann was looking for staff for a post-doc project,” she says. “I knew Ms. Brüggemann from my master’s studies, had heard talks of hers, and read up on her field of work.” The Emmy Noether award winner Brüggemann carries out research on nano-biomaterials with her working group at the Institute for Biophysics. One of the things she has done is developed a three-dimensional protein scaffold that could help with wound healing in the future.

Nanotechnology and biochemistry: These are the fields that Arundhati Joshi was familiar with. The only difference is that it is about nanofibers and their interaction with cells now. “We investigate the production and application of bio-inspired nanofiber networks. The aim is to one day create a type of ‘biological wound covering’ from the blood of the person that needs the covering,” explains the post-doctoral researcher. Her main task in the current project is to assess the interplay between nanofibers and cells, especially skin cells.

© Titinun Nuntapramote

Three Months of Working from Home Instead of Laboratory Sessions

The corona pandemic broke out in the middle of this complex research. “I had just really got going in the spring of 2020 and was suddenly no longer allowed to go into the lab for three whole months. I was, however, able to use the time well when working from home and contributed to the completion of a research article and new review article that summarizes the status of research in this field well.” What is the field like, what has been ascertained already, and what is still missing? “This work helped me a great deal in diving deeper into the topic. Despite this, I still missed the laboratory work that I really like - as well as talking to other researchers.”

In comparison to the first lockdown, Arundhati Joshi has been able to spend far more time in the lab this year. Not in the same way as before the pandemic of course: Rooms that are usually used by three or four people at the same time - for example when working on cell cultures or microscopy - were only allowed to be used by one person if they had booked the room. Thanks to the Emmy Noether funding from Dorothea Brüggemann, her position has been secured until May 2022.

“It seemed really empty to me here in Bremen at the beginning. I thought that there were no people here.”

Corona also influenced her private life. “My fiancé really helped me the whole time. He was my biggest supporter during the time spent away from my family.” Usually, Arundhati Joshi spend several weeks in India at least once a year. But that didn’t happen and her last visit there was in August 2019. She is only able to maintain contact to friends and family via digital channels. Arundhati Joshi is thankful that most of her relatives and friends in Pune have not been affected by the pandemic that is raging there: “They’ve all been in quarantine for months now.”

Initial Culture Shock in Bremen

The initial time spent in Germany was a culture shock for her. India has nearly 1.4 billion inhabitants: “It seemed really empty to me here in Bremen at the beginning. I thought that there were no people here” she says and grins. It was cold and dark in the winter and the food was strange: That’s also something that you have to get used to. However, Arundhati Joshi has settled well now. Where her path will lead her is unsure, as scientific assistants often have to come across the right opportunities at the right time. “Habilitating is too much for me - I won’t go down that route,” she states with certainty. “However, I would like to remain in the field of scientific research in Germany. I think I’ve got better chances here than elsewhere.” That may be the case. After all, Germany did choose her.