© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

“I Couldn’t Imagine Having a Normal Job”

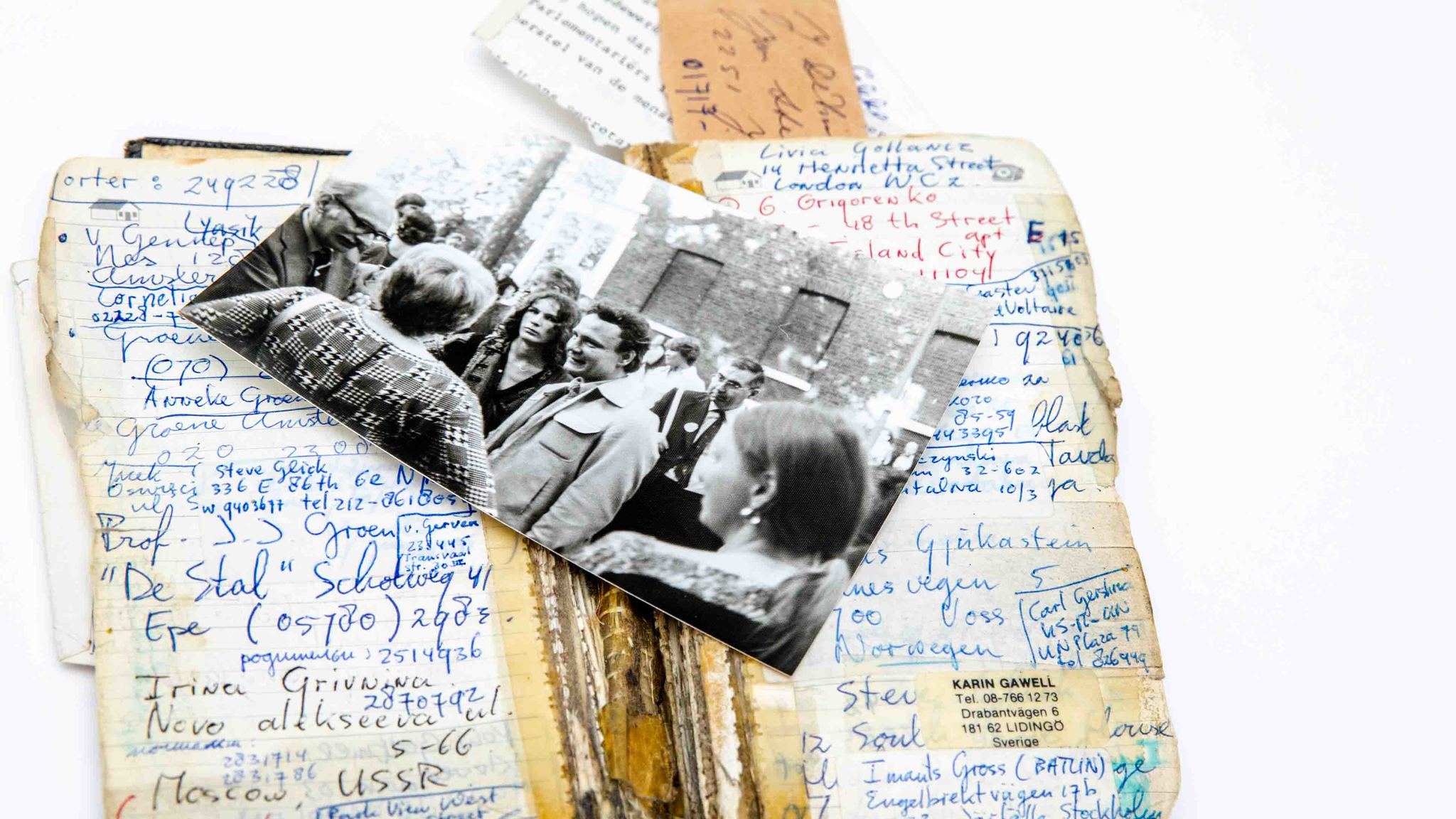

Human rights activist Robert van Voren tells us of his time as a courier for political dissidents in the Soviet Union

In the 1980s, the human rights activist Robert van Voren regularly travelled to the Soviet Union as a courier and smuggled information from and about the politically persecuted into the West. A part of his lifetime bequests is currently kept at the Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO). In this interview, he reveals how he became a courier, why being surveilled by the KGB was sometimes useful, and who wore his winter coat.

How does a Dutch history student turn into a courier for the politically persecuted in the Soviet Union?

In the 1970s, my father awoke my interest in the Soviet Union. I read a great deal about it but still had many questions. In 1976, Vladimir Bukowsky was expelled to the West and I decided to write him a letter with 44 questions. Surprisingly, he replied. We started to write to each other and became friends. In 1978, I flew to London to visit him. He introduced me to Peter Reddaway, a professor at the London School of Economics, there. He was the central figure in sending couriers to the Soviet Union. Bukowsky had the following idea: I was to complete my degree and then move to Moscow as a journalist. That was how I was to function as a postbox.

It turned out differently though: You fled to Leningrad – which we now know as St. Petersburg - as a courier at only 20 years of age. What happened?

During my Sovietology degree, I became friends with a dissident from Moscow. We spoke on the phone once a month and in February 1980, he said: “Robert, if you want to see a dissident, you need to come because they are arresting us all.” That is when I decided to wait no longer but rather travel to the Soviet Union straight away. He was arrested on the day that I booked my trip. It was only after his release four years later that we met for the first time. That’s how it all started.

But what really changed my life was an experience during my second trip to Moscow in March 1980. Basically, everyone who I met during the trip was arrested. Several of them even whilst I was still in the Soviet Union. And that’s when I met the Estonian ornithologist Mart Niklus. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison and exile for his contribution to the so-called Baltic Appeal, which demanded the reestablishment of the independence of the Baltic states from the Soviet Union amongst other things. I simply couldn’t imagine having a normal job whilst he was in prison. So, I swore to myself that I would do this work until his release.

What did your family think of your plans?

My mother was elated – her brother had fought against the national socialists and she saw my dedication as a logical continuation of that.

What exactly was the courier service like?

My job was to take aid packages to the Soviet Union and return with information. I often travelled disguised as a tourist in a travel group. Russian dissidents and their families were to be helped in this way: whether they were in a prison camp, in exile, or in freedom. I took varying aid supplies with me on the outbound flight: thermal underwear, warm clothes, medication, vitamin tablets, and stock cubes in order to improve the nutrition of the people in the prison camps. In the winter months, I always wore a new coat on my arrival, which I was then able to gift. In the winter of 1984, the Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov wore my coat. I was very proud of that.

I brought information back with me: It was about the oppression, arrests, and convictions of the dissidents. I also smuggled self-published literature, so-called samizdat, which did not conform to the system, through the Iron Curtain.

How did you manage to get the texts out of the Soviet Union?

I learnt several of the texts by heart and I photographed others with slide film. In contrast to color or black-and-white film, slide film could not be developed and viewed quickly enough at the airport prior to departure. As an additional means of safety, I rerolled the films and placed them back in their packaging. I regularly left the Soviet Union with ten to twelve “unused” slide films. When they carried out a strip search, the films were in my travel bag on a table and passed through the checks unnoticed. I developed the films back in the Netherlands, printed the slides, and distributed them all over Europe using address lists.

Were there other couriers apart from yourself?

Since the 1960s, couriers travelled to the Soviet Union several times a year, for example to Moscow, Kiev, and Leningrad. They were essential for the connection between the dissident movements and their Western supporters. In the 1980s, we couriers had contact to each other and planned our trips to the Soviet Union in such a way that one of us travelled to the USSR once a month. We also used the network to distribute information and warn each other. One of the couriers was poisoned on a flight. Afterwards, we decided to no longer eat or drink anything in public.

What was your first impression of the Soviet Union?

Fear! I was extremely scared when I arrived in Leningrad in February 1980. I had no idea what was waiting for me behind the Iron Curtain and I saw KGB agents everywhere. It was only three years later, when I was arrested, that I was able to let go of the feeling. I had a meeting with the Independence Peace Movement in Moscow. As the flat was tapped, we went to a park. There were a surprising number of people stood next to the trees to relieve themselves. We were surrounded before I was able to realize what was happening. We were taken to the station in two police cars and were questioned. It was there that I realized that the agents were normal people just doing their job. I saw their faces. The KGB lost its mystique for me and my fear disappeared.

I was even able to find some good in being surveilled by the KGB during later trips: I always had bodyguards with me. I especially felt safer when I was in districts on the edge of town at night. When I was observed less and less in 1988 and 1989 – during the Soviet Union reforms – I nearly felt unprotected. That’s how very used to them I had become.

The Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen is keeping many of your documents as lifetime bequests. How important is the work of the FSO in your opinion?

The FSO is of great significance, especially for future generations. I think that we only have a future if we are aware of our past. The archive not only holds books and documents but also personal effects from real people who became dissidents by coincidence or deliberately.

There are reasons for which my lifetime bequests are here at the FSO: They are safe in Bremen! The NGO Memorial in Moscow was interested in my archive, but it wouldn’t have been safe there. I made a good decision with Bremen.

About FSO

Since its establishment in 1982, the FSO’S independent archive has had the goal of collecting and researching testimonies of critical thinking in Eastern Europe. Today, the archive holds a worldwide unique collection of more than 600 lifetime and posthumous bequests from former regime critics, human rights activists, authors, and artists from the former Soviet Union. Unique compilations of samizdat literature, flyers, and underground stamps from Poland and former Czechoslovakia have been comprised. Smaller collections also originate from the GDR and Hungary.

Sources such as those that Robert van Voren smuggled into the West in the 1980s are part of an archive-indexing project that the Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO) at the University of Bremen has been carrying out since 2019 and which is being funded by a grant from the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship. The aim of the project is to make the materials of the politically persecuted and soviet prison camps in the FSO archive accessible as quickly as possible and to prepare it for research.