© Sarah Batelka / Universität Bremen

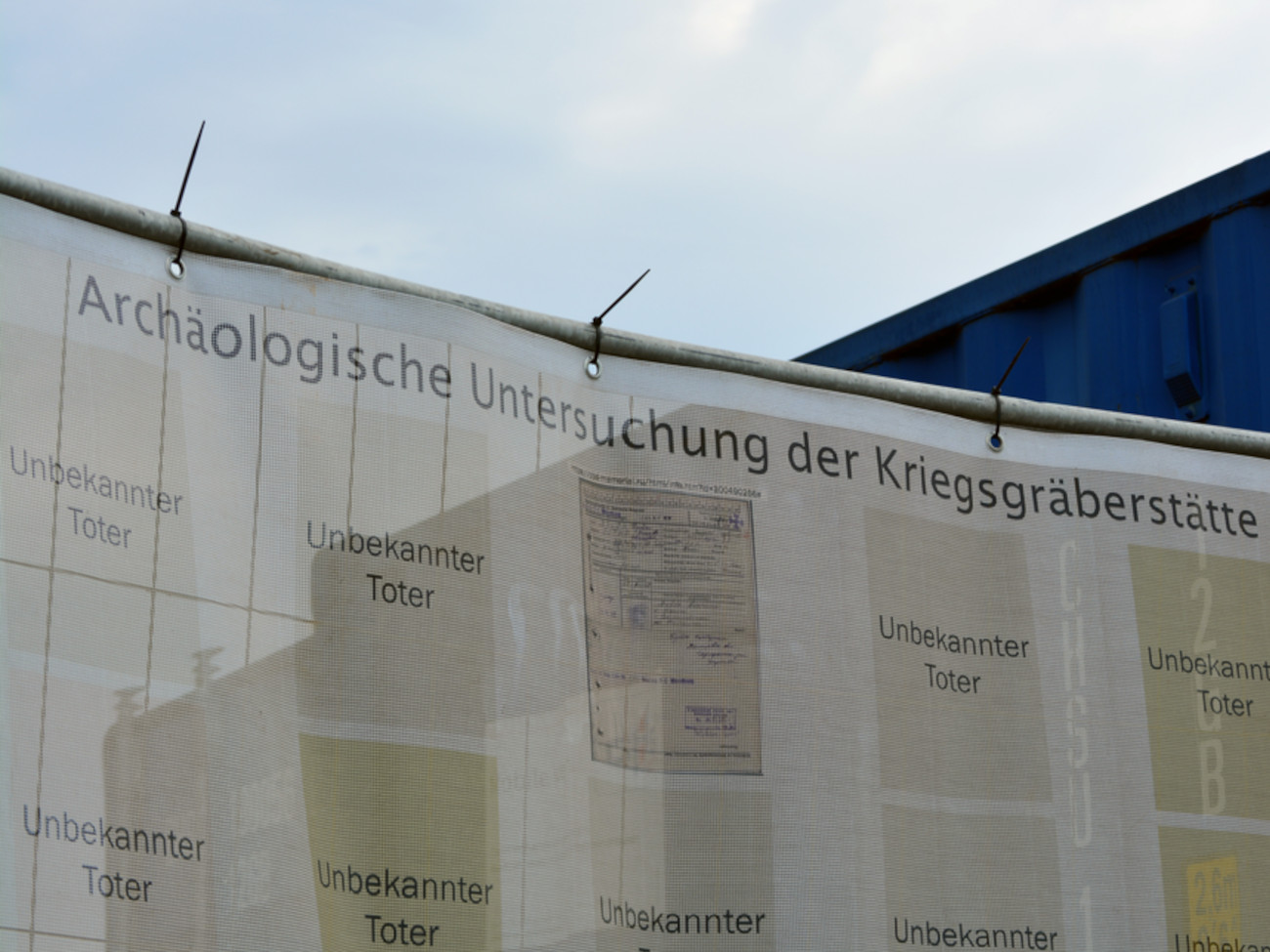

Excavation at Former Cemetery for Soviet Prisoners of War

History students engage in an extraordinary project led by the state archaeologist.

Uta Halle is Bremen’s state archaeologist and a professor at the University of Bremen. For a year now, Professor Halle and her team have been excavating a former Soviet prisoner-of-war cemetery from the Second World War in Bremen’s Oslebshausen district on behalf of the state government. The site is home to the remains of war victims, forgotten for almost 80 years. It was only by chance that the excavations began at this spot, which is located in a dusty industrial area. In their efforts to prevent a railway workshop from being built, a local citizens’ initiative came across the cemetery during their research of the site. An interview with Professor Uta Halle.

Ms. Halle, when did you start your excavation work at the former Soviet prisoners-of-war cemetery from the Second World War in Bremen’s Oslebshausen district?

We started preparing for the excavation work in July 2021, meaning we removed two meters of war debris first. We then dug in the first rows, finding the first bones and the first identity tags of those buried. These identity tags gave us the valuable clues. In actual fact, no bodies should have been found here, because the war cemetery had been closed down in 1948 and the deceased had been relocated. But as it turned out, this had not been done properly. There was also a map of the cemetery site from the 1940s. It soon became clear that corpses had been overlooked during the relocation to the cemetery in Osterholz. That’s why we were commissioned to dig here.

What have you found so far?

We’ve found 14,000 bone fragments to date, including individual fingers, kneecaps, and the like. These bones are important keys to the past. For example, we can tell from the kneecap whether someone has been buried on their stomach or on their back. The teeth or the cranial bone can be used to estimate the age of the corpse. The cemetery was not fully exhumed in 1948, so we seldom found complete skeletons at first. There are now 65 skeletons, and we found 203 identity tags. These findings have been used to identify 150 people, by which we mean we have the names and the nationalities.

© Sarah Batelka / Universität Bremen

How many corpses are there under the soil? And which countries did these people come from?

The victims were citizens of the former Soviet Union and came from areas that are now part of Russia or Ukraine. They are predominantly Russians, but there are also Ukrainians and Belarusians. So these were Soviet prisoners of war, as well as forced laborers who probably came from Poland. A police report from 1946 lists the numbers of 217 graves with wooden identifiers, other graves with abbreviations Z1 to Z63, and 460 gravesites without identifiers. But at the moment we assume that these gravesites were not occupied, because old aerial photographs show us that there were two cemetery sites of different sizes with a light area of sand between them.

© Sarah Batelka / Universität Bremen

How do you go about your work?

We work inch by inch. Each layer is uncovered with the utmost care. We are currently working on a gravesite with several complete skeletons. Removing everything around the bones is a special task that requires a great deal of care and patience, but we also work with excavators. We’ve already worked our way down to a depth of six meters. Now we have reached the last corner of the cemetery. In the first part of the cemetery, we found some gravesites. In the meantime, we also found several mass graves. The bones of 16 people are visible in the field from which we are currently recovering the corpses. In another field, we expect to find 20. But we see further differences compared to the first gravesites. These people were buried undressed, while the bodies in the first graves were partially clothed. They are tightly packed together.

What does that say about possible causes of death?

We’re not at the stage of interpreting yet, we’re still collecting. The scientific documentation and subsequent evaluation are very complex, but we do know that there were four internment camps here. The forced laborers were put to work in road construction and in armament factories such as AG Weser. Many died due to disease, exhaustion, prison conditions, or were killed in Allied bombings.

How important is this find for Bremen?

Our excavations in Oslebshausen represent a very important find not only for Bremen, but also for Germany and even Europe as a whole. By the end of the 1940s, many cemeteries had been closed down and the dead had been reburied. As you can see, things didn’t go to plan at this cemetery after the war, because it was only partially exhumed. And now people are beginning to wonder whether there are similar cases in other countries as well. We went to Linz to present our work at a conference organized by the Austrian Society for Medieval Archaeology, attracting a great deal of interest from experts.

Students from the University of Bremen are also involved – this is certainly an interesting topic for research-based learning.

Indeed it is. Last year, we had 25 students from the history bachelor’s program, as well as one student from environmental history, who wrote his master’s thesis on the landscape development of the site around the cemetery. In addition, four students from Kyiv helped us out, as well as others from Berlin and Hamburg. Of course, our excavation was also the subject of bachelor theses. Project work also covered the situation at the site and the Soviet prisoners of war, which we displayed as posters during the “Tag des offenen Denkmals” (“day of the open memorial”) event.

Were you able to locate any relatives of the deceased?

Yes, we found relatives in two cases, which were children and grandchildren or nephews. It was a very moving moment for us, and it’s extremely rare to experience such a thing in archaeology. The people I’m usually occupied with have been dead for hundreds of years. This is something very special – their life stories could be traced through the trail of the identity tags. We can give the dead their identities back.

© Sarah Batelka / Universität Bremen

What will happen to the remains that were uncovered?

It is over to the politicians to decide. The finds are first are sent to the state archaeology authority, where we carry out further analysis until a decision has been made on what to do with them. The Bremen state government is in talks with the consulates general of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

What do you think should happen to this site on the Reitbrake? Would it be a worthy memorial?

If you’re asking me for my personal opinion, then no. Look around you. Next door is Bremen’s hazardous waste storage facility. There’s also a horticultural company, a block of apartments, the railroad, an oil storage facility. It’s the place the Nazis chose for it back in 1941, knowing full well that it was to become an industrial area. This place is not worthy of such a memorial. And there is a suitable place in Bremen – the cemetery of honor in Osterholz. I could imagine the memorial site being there, but I would also like to think that information from the excavation will be added to the small memorial site on the Reitbrake.